Nearly 30 years after the opening of “The Real Estate Show” — the legendary guerrilla exhibition that took over an abandoned storefront on the Lower East Side in protest of neighborhood gentrification and eventually spawned ABC No Rio — self-proclaimed white cubes are saturating the middle-ground between the gritty exterior and the meta-façade of two ‘unmonuments,’ ABC No Rio and the new New Museum. The intensity with which contemporary art is laying claim to morsels of space (however untenable they may appear) evokes a radical allusion to Gordon Matta-Clark’s infamous Fake Estates of 1973–74. The project, for which he purchased from the city 3,500 square feet of left-over, in-between, barely measurable or otherwise abject plots — including a bit of sidewalk, a piece of someone’s driveway, or a section of curb — seems a retroactive hyperbole, both parts political and poetic, for this moment’s extreme commodification of downtown space.

The Fake Estates have been described as “anti-property” — a term that would be at odds with the role of a successful commercial gallery.1 And yet, many such establishments that have recently opened, relocated, or formed satellites on the LES are extracting new meaning from the frenzy by re-popularizing a degree of misbehavior along the fault lines of the area through their concept, program or operation.

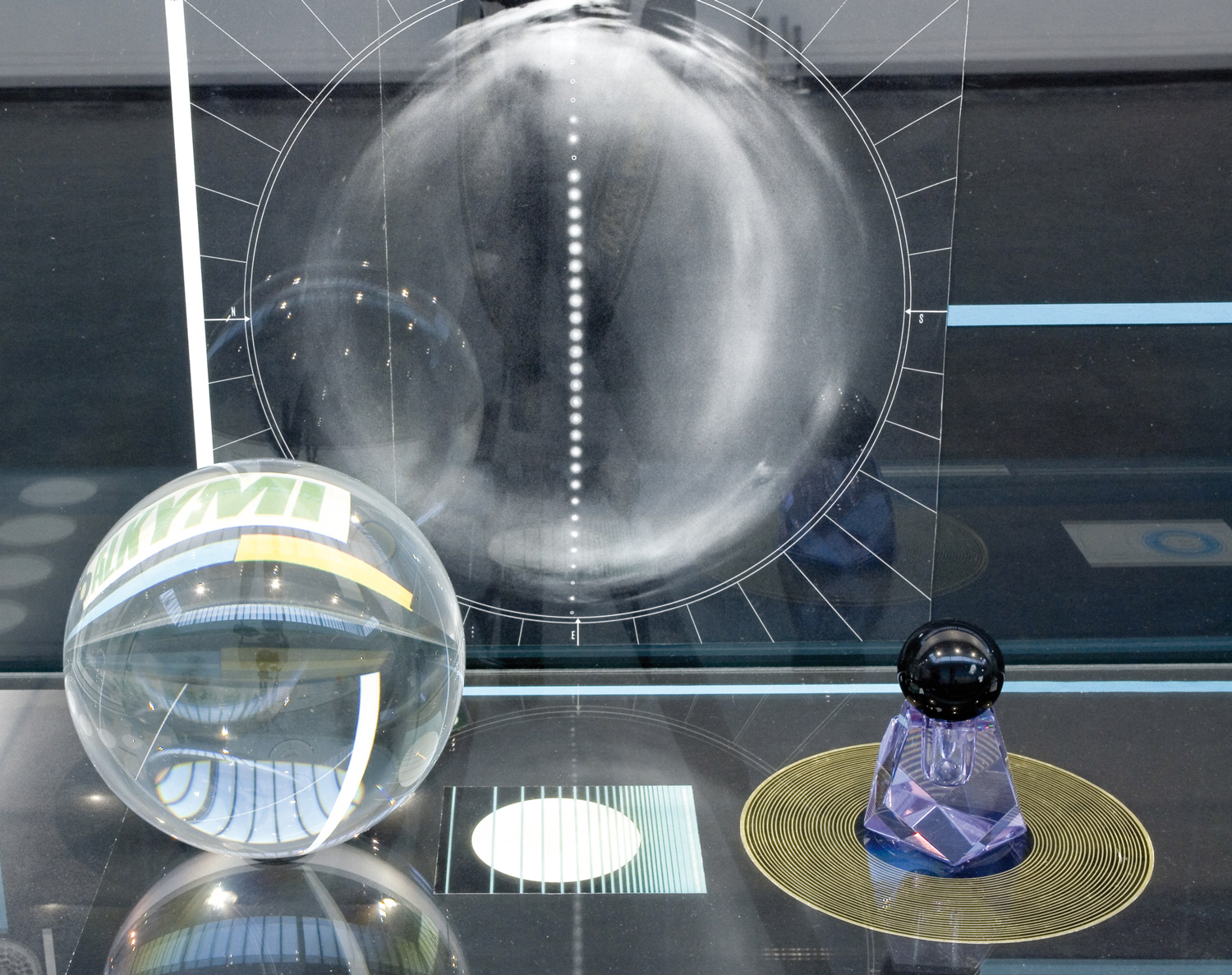

Fruit and Flower Deli, which opened late in the magically long summer of 2007, centers its thesis around a mythological parable. The proprietor (Rodrigo Mallea Lira — “the Keeper”) and his partner (artist Ylva Ogland — the muse/goddess/Snöfrid, the art magazine which “has evolved from a vague idea to a persona”) have constructed an intricate yet understated otherworld that is at once private and remains at your disposal. The gallery’s website advises, “If you would like to pay a visit to Fruit and Flower Deli, it is recommended to email the Keeper for help before, since Fruit and Flower Deli is never open, nonetheless you are always welcome.” The site alone is so performative it nearly functions as an intervention, its exhibition history verging on scripture.

On the subject of holiness and accessibility, Texas-based independent curator Clayton Sean Horton also had a splendid notion last year: starting a New York gallery that would be open on Sundays, called Sunday. Located in a residential building, Sunday defines itself as humble and domestic, providing an “intimate, casual environment for viewing art.” What Sunday and Fruit and Flower Deli have in common (aside from cute names and the intersection of Stanton and Eldridge) is their shared emphasis on exhibitions. These clever enterprises, together with Smith-Stewart, James Fuentes, Thierry Goldberg, Canada, the recently transplanted Luxe Gallery, and LES staple Rivington Arms, comprise a demographic of galleries for which selling art truly appears secondary to presenting new work.

This could be due in part to the curatorial background of an increasing number of gallery-owners. For example, Amy Smith-Stewart curated exhibitions at P.S.1 Contemporary Art Center, the Norton Collection, and Mary Boone Gallery before launching her own gallery. Likewise, dealer James Fuentes is a Bard alumnus. He co-created Artstar (the unscripted TV series that documented a collaboration between eight artists in consultation with downtown veteran Jeffrey Deitch in 2006) while organizing exhibitions beyond the space that bears his name, such as “Programming Chance” at The Emily Harvey Foundation — a group show that unexpectedly brought together the work of Allison Knowles and Aaron Young in 2007.

Coexisting with galleries on the LES is a live culture of intuitive, protean spaces that foster experimentation, associative dialogue and spontaneity. Orchard, a cooperatively organized exhibition and event space run by 12 partners including Andrea Fraser, is a three-year interdisciplinary undertaking that will close in April 2008. Perhaps the most exciting thing to happen to institutional critique since The Wrong Gallery, this trim yet wildly discursive environment has integrated the work and ideas of such defector-luminaries as Daniel Buren, Hans Haacke, and Martha Rosler with those of elusive personages like Artur Barrio and Anastazy Wisniewski. (The title of Christian Phillipp Müller’s current exhibition, “Cookie Cutter,” can’t help but murmur something under its breath about the “pre-fab” sea of corrugated metal and glass surrounding the gallery that ultimately begs the question, who sucked out the feeling?)

But before Orchard there was Participant Inc., a rare life force whose primary mission — to serve artists — has indisputably withstood the test of time and displacement. Following the loss of its Rivington Street location (where it had been since 2002) to rent increases, Participant has unveiled its new home on Houston Street. An exhibition called “Technically Sweet,” co-curated by Denmark-based artists Yvette Brackman and Maria Finn, inaugurated the building in January of this year by inviting a group of artists to interpret the ‘completion’ of an unrealized Antonioni script. The choose-your-own-adventure model of the project, which has an accompanying film component at Anthology Film Archives, befits the constant changeability of the LES landscape. Embracing artists as curators is a practice characteristic of Participant (please refer to Blow Both of Us, co-curated by Adam Putnam and Shannon Ebner last year).

It’s also worth mentioning that Participant is one of few LES institutions in the past decade that have consistently hosted performances, which means trusting artists enough to produce acts that, even as they occur, anticipate their own inevitable non-existence. Appropriately, founder/director/curator/prophet Lia Gangitano activated her new space with a Performa07 production by playwright Tom Cole and the artist duo Lovett/Codagnone a month before her official re-opening vernissage.

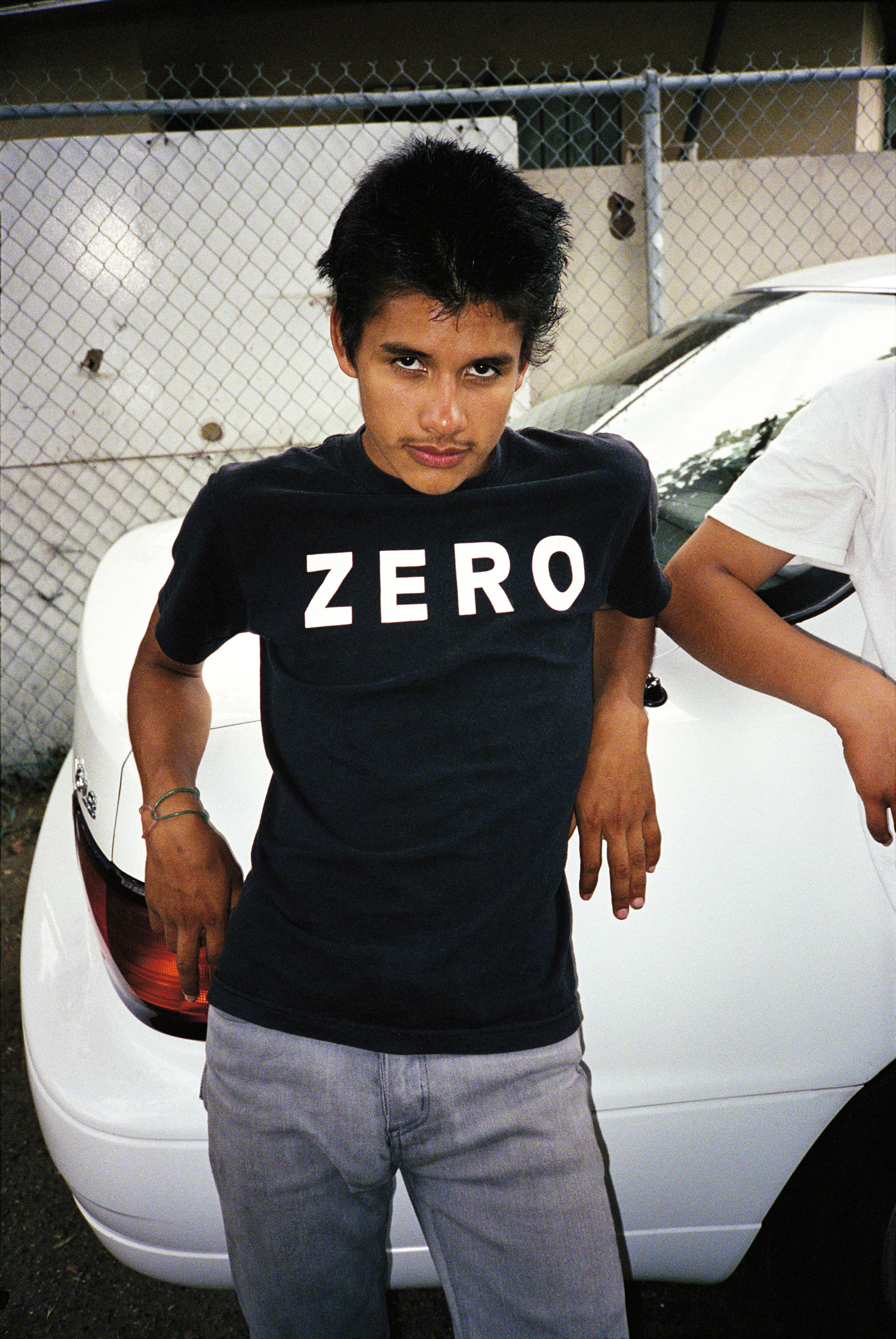

Another entity that has supported performance is Reena Spaulings Fine Art, conceived of by artists Emily Sundblad and John Kelsey in 2004. Shirking any obligation to define itself, Reena Spaulings is polymorphously perverse; its namesake, sometimes a fictional artist with actual gallery representation, is also a collective, a dealer, a plucky protagonist, and a frame of mind. At the opening of his 2007 Reena Spaulings show, Merlin Carpenter painted messages that grossly defaced the whole business of his being there, like “die collector scum” and “Relax, it’s just a crap Reena Spaulings show.” Like ‘safe words’ in a masochistic fantasy of self-effacement, Carpenter’s aphorisms brought us back to a reality where we’re exceedingly aware of the systems, codes and agendas of gallerists, collectors, viewers, and not least of all, artists, alike.

Of course it’s possible to dismiss such staged opposition, especially when profit is involved, as a byproduct of the standardized values that come along with ‘yuppification’ — but the truth is, no matter how commerce-driven its development, the LES renaissance is generating new wonders. Galleries like Never Work and V&A are popping up; these are small, focused spaces that represent a handful of artists. Rental invites galleries from all over the world to “rent” its exhibition space, promoting international exchange, temporariness, and opportunities for artists to broaden their audiences. Further, many longstanding galleries have found sanctuary in LES annexes that complement their primary locations, among them Salon 94 and Greenberg Van Doren from uptown, Lehmann Maupin from Chelsea, Jack Hanley from LA, Museum 52 from London, and more on the way.

While the temperament of today’s refurbishing LES is a far cry from the agitation catalyzed by “The Real Estate Show” in 1979–80, downtown exhibition spaces are making markedly original things happen.