On entering “Move: Choreographing You” at the Hayward Gallery, it’s best to leave preconceived ideas of normal gallery behavior at the door, along with any items of clothing that may prove restrictive. The exhibition aims to loosely trace the relationship between art and dance stretching back over 60 years, with all works linked by the participation of the spectator. Viewers are invited to become a part of the work, to experience it physically as well as cerebrally. The atmosphere is transformed as a result: silent contemplation is replaced by enthusiastic laughter and chat among visitors.

It all takes a bit of getting used to. The show leaves little time for such acclimation though, opening with Bruce Nauman’s unsettling sculpture Green Light Corridor (1970), a narrow, open-ended passageway bathed in fluorescent green light. It can only be entered sideways, and claustrophobia descends quickly. Once released from its luminous clutches, visitors are plunged into the pitch darkness of the opening chamber of Lygia Clark’s installation The House is the Body (1968). Penetration, ovulation, germination, expulsion. Intended to emulate the phases of conception, pregnancy and birth, the work asks viewers to pass through various ‘cells’ offering different sensory experiences.

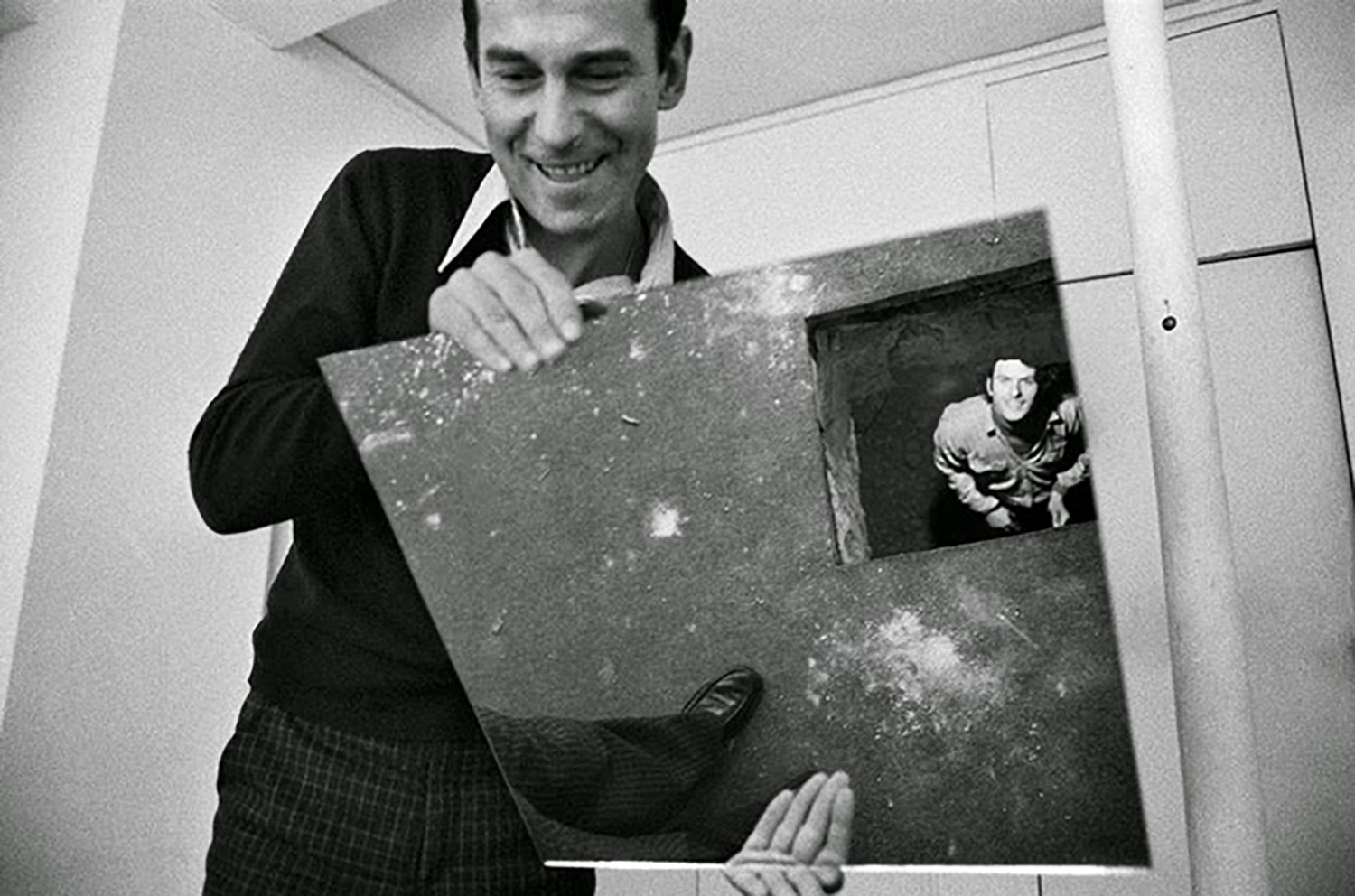

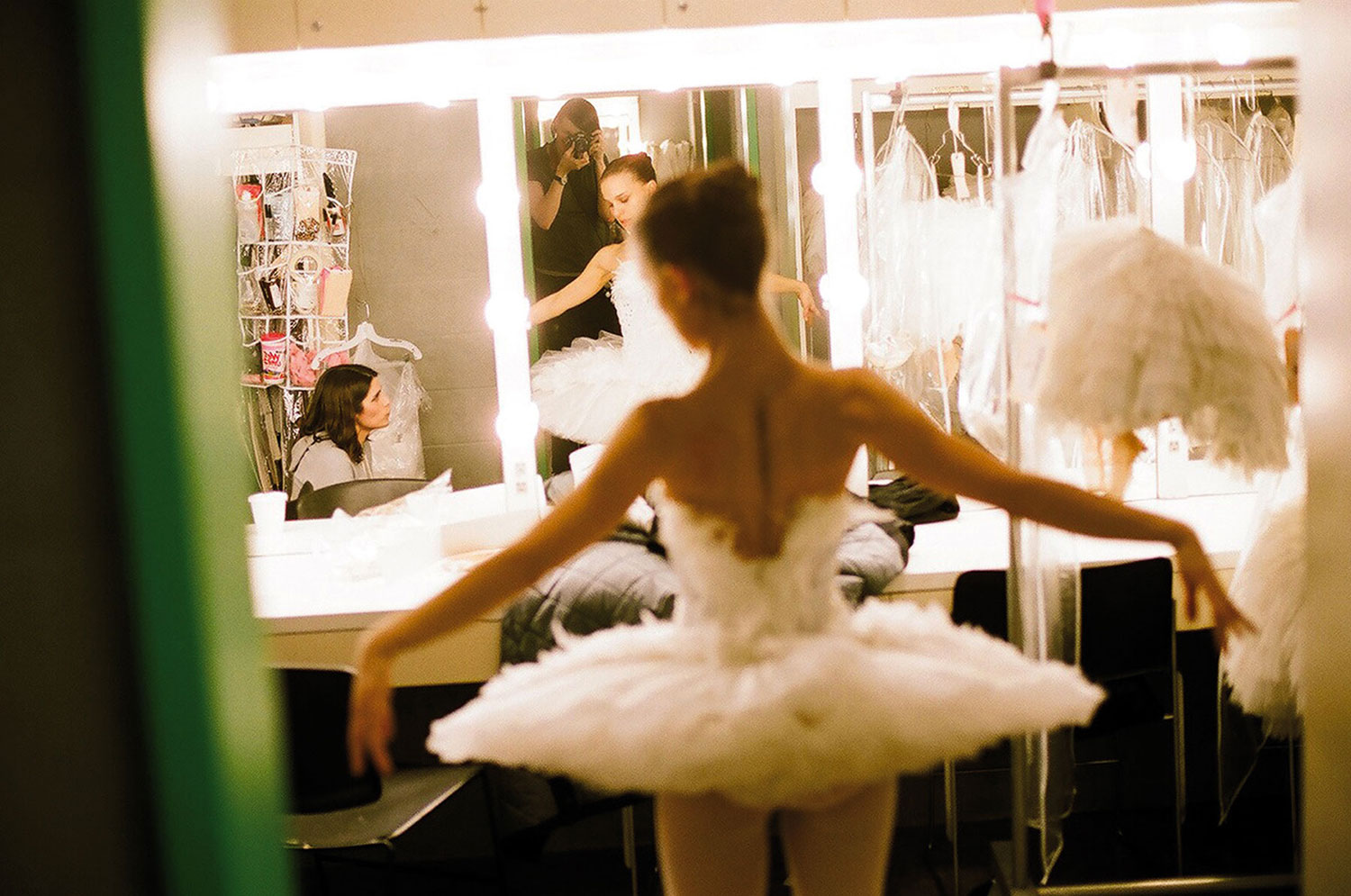

Having limbered up with these pieces, the true physical work begins, as William Forsythe challenges gallery-goers to traverse a space without touching the floor, by the use of a series of gymnastic rings. Elsewhere, examples from Robert Morris’s landmark “Bodyspacemotionthings” (1971) sculpture series test the balancing skills of participants. These pieces become as much fun to watch as be a part of, and the interactions mean the exhibition is constantly in flux. This sense of the unexpected is reinforced by a series of interventions by dancers and performers who appear in the gallery space unannounced throughout the day. There are also plentiful examples from the history of dance and performance art to be found on the extensive digital archive accompanying the show. “Move” is ambitious, moving beyond dance to explore other aspects of the experiential in art. Experiments in video art are explored in a number of works: an installation by Boris Charmatz offers a theatrical televisual spectacle designed for just one person, while in Dan Graham’s Present Continuous Past(s) (1974) a neat trick with a two-way mirror and a video camera places visitors at the center of the very work they are viewing.

Tania Bruguera’s installation Untitled (Kassel) (2002) is intensely uncomfortable, with participants blinded by a bank of lights and subjected to the sounds of a gun being loaded, though its political message is somewhat undermined by its proximity to Christian Jankowski’s cheerful hula-hooping film Rooftop Routine (2007), which greets visitors upon exit. And Isaac Julien’s epic new video installation about the deaths of the Chinese cockle pickers in Morecambe Bay proves similarly awkward here, requiring a degree of concentration and thought difficult to achieve in such a demanding show. The most successful moments are therefore those that exercise the physical senses: “Move” offers excellent opportunities for play, but little time for deeper reflection.