The Berlin photographer Michael Schmidt’s work is some of the most significant and at the same time least well known in postwar German art. Schmidt is committed to an approach that depicts reality, but not in an objective manner, such as in the photographs of Bernd and Hilla Becher for example; he translates his material into a radically subjective, highly disturbing pictorial language. Schmidt’s work circles around German history and states of mind, focusing on his home city, Berlin. He is a trained policeman and a self-taught photographer. It was probably his best-known work today, Waffenruhe (Ceasefire), created between 1985 and 1987, that finally helped him to make an international breakthrough, after over two decades of intensive photographic work. Waffenruhe is in many parts, presented in tableau and constantly rearranged. It can be seen as a kind of mental description of a condition, translated into images using photographs taken in the early 1980s in West Berlin. But even though the Wall, and hence Berlin, can be identified in many of the pictures, Waffenruhe does not present a record of the divided city.

The work does more than relate to a concrete time and political situation. It is to be understood as a metaphor for an intellectual and emotional condition of being, for mourning, loss, hopelessness and rage, which Schmidt reveals through the urban landscape, maltreated and wounded to the quick, and through its inhabitants.

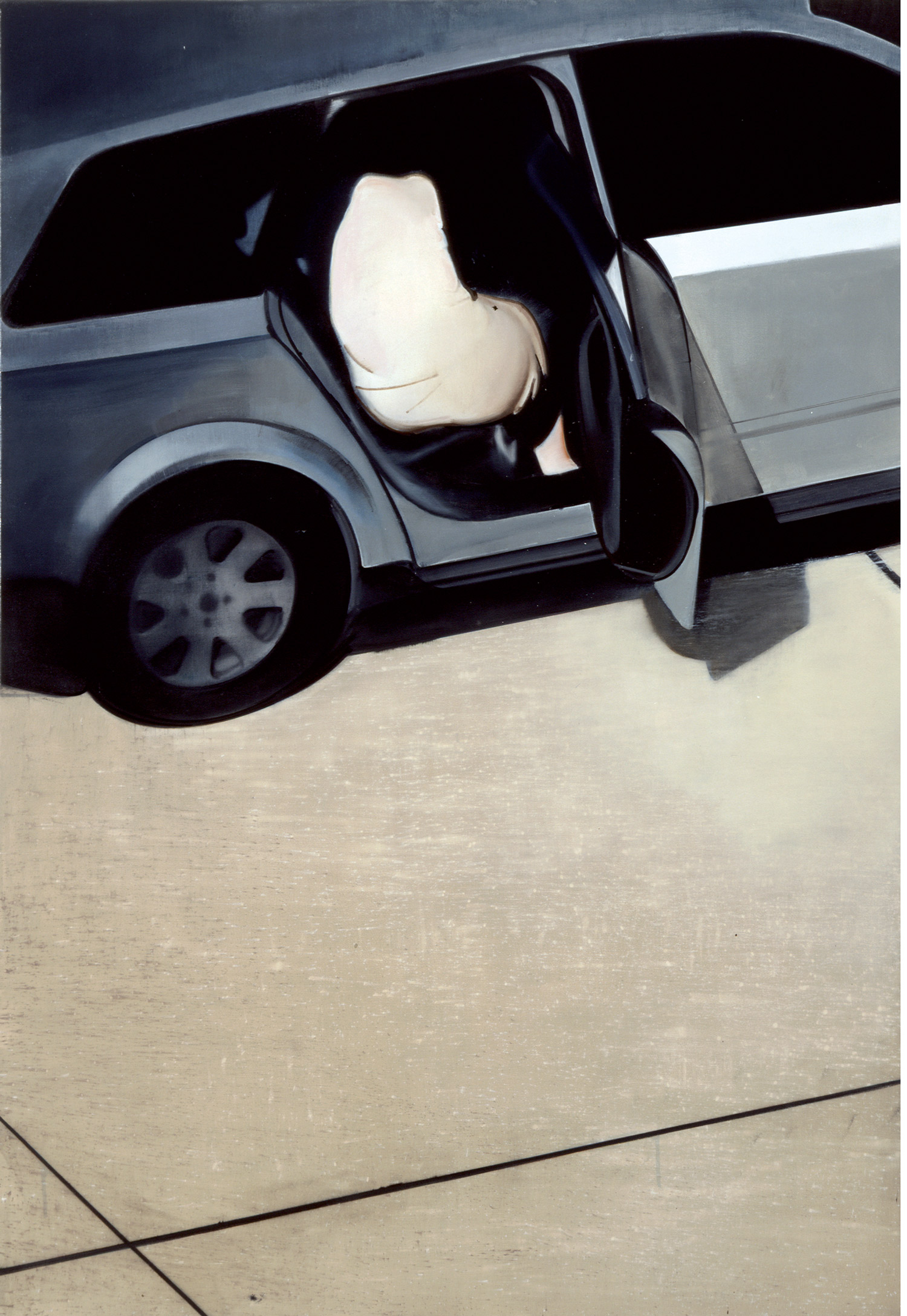

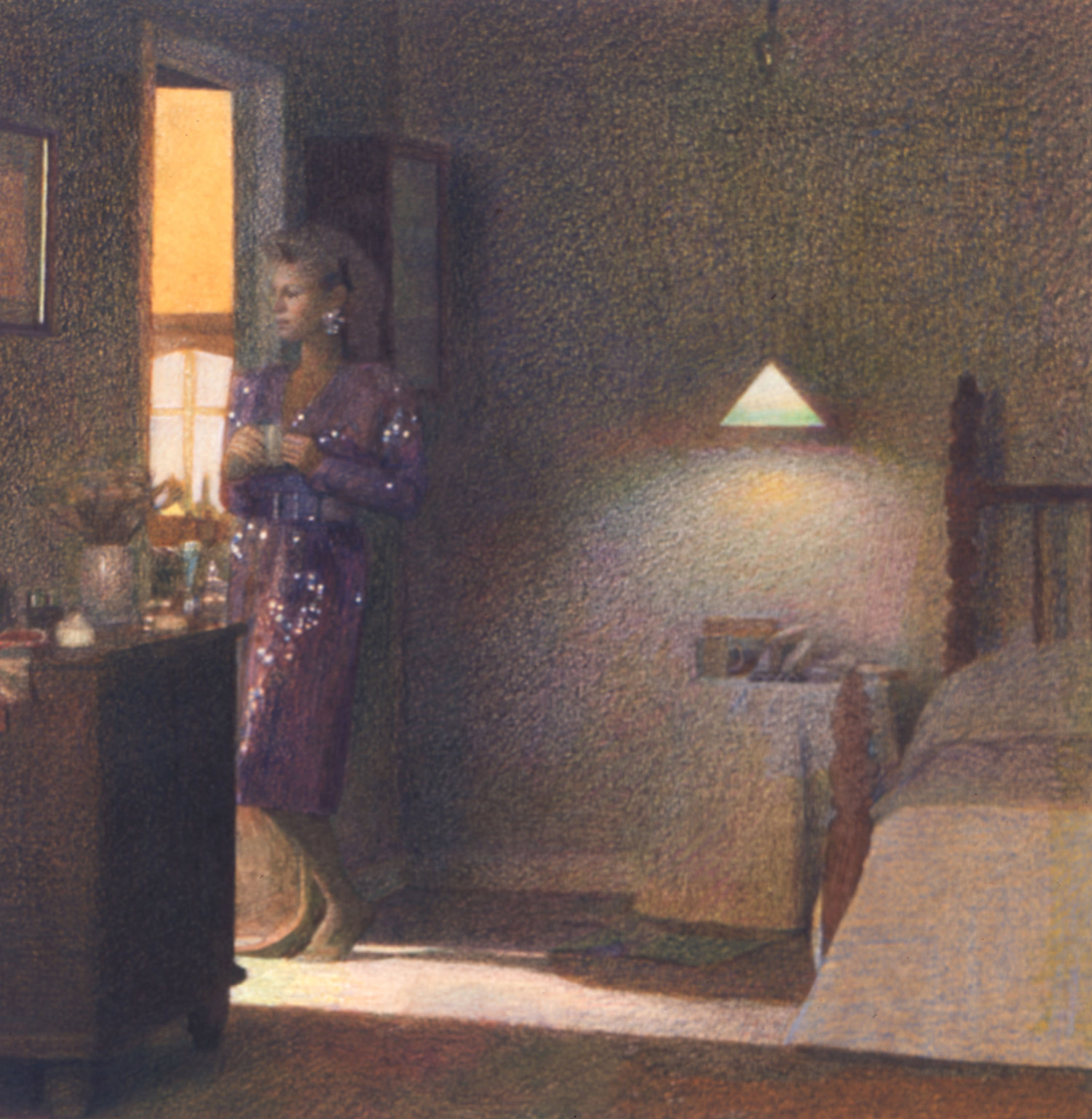

The series of works called Ein-heit (U-ni-ty) dates from 1991 to 1994 and includes about 160 photographs. Here Schmidt combines his own photos with pictures by other photographers, usually anonymous. Each picture is enlarged to a 50 x 35 cm format, framed in iron, and presented in a tightly packed sequence. Viewers are surrounded by a series of pictures that can be repeated almost to infinity: dreary city views, tower blocks, landscapes, still lifes made up of everyday objects and anonymous portraits, all taken by Schmidt in the early 1990s, the period immediately after the fall of the Wall, and mixed with reproductions of historical photographs. The latter show mass rallies, portraits of politicians or historical events, and are to be read as set pieces and scraps of memory relating to German history in the 20th century: one common history under the Third Reich, and one divided into East and West. Images that seem familiar, drawing on our collective memory, have been cropped, alienated to the point of unrecognizability and broken down into crude half-tone dots. In contrast with Waffenruhe the tonal range is lighter, and the photographs that are not reproductions are pin-sharp. But this entire conglomeration of fragments, scraps of memory, images and references to images remains disparate, fragmentary, cannot be fitted together as a unit. The individual and society, the forgotten and the remembered, the present and history are juxtaposed abruptly, with the artist standing in between. Schmidt refuses specificity, any clear classification, any generalization. Both the book of the same name and the exhibition create mental and visual empty spaces, abrupt breaks; viewers have to relate the images to each other themselves, and each person does this differently. Ein-heit refuses to make any moral judgments, but asks questions about social and personal identity in a country that perceived itself as divided for the preceding five decades and whose infamous past before that, between 1933 and 1945, still militates against any attempt at positive identification, against establishing an identity in general.