“In 1990 We Spoke about Freedom, Now We Speak about Money.” Dan Perjovschi’s pertinent words on the condition of contemporary Europe greet me at the entrance of the new Muzej Sodobne Umetnosti Metelkova (Museum of Contemporary Art Metelkova) in Ljubljana, Slovenia. The museum is situated in a renovated army building in an area of the city that has housed its alternative scene since the early ’90s. It is the first time that I’ve been back since the European biennial Manifesta in 2000, and reconnecting with this city also means revisiting an intense and turbulent period in recent European art history. In fact it was during the years after the fall of the Berlin Wall that a dynamic exchange between the Nordic art scene and the new networks in East and Central Europe took shape. Artists, curators, independent magazines and art spaces were the main generators of these links. An important exhibition introducing a new generation of artists from this region was “After the Wall: Art and Culture in Post-Communist Europe” (1999) curated by David Elliott at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm. It is also worth noting the importance of the now-closed Nordic Institute for Contemporary Art. Reflecting on a possible identity for the Nordic art scene today, it is important to remember how active it was at that time as a meeting point and hub for ideas, expanding the then-established geopolitical borders of the North.

The late ’90s and early 2000s were years when the Nordic art scene went through a period of intense internationalization, starting with artists and curators initiating networks and exchanges between smaller institutions, art fairs and magazines. It was an internationalization that was later fueled by government-founded institutions with an agenda to put Nordic artists in touch with the international community. One of the most important and memorable moments of the courtship between the international art circuit and the Nordic sphere was of course “Nuit Blanche,” an extensive show at the Musée de l’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris in 1998 curated by Hans Ulrich Obrist and Laurence Bossé. It was also Obrist who, with eloquent timing, coined the term “The Nordic Miracle,” sparking international interest in artists like Finnish Eija-Liisa Ahtila, Elmgreen & Dragset (respectively from Denmark and Norway), Swedish Ann-Sofi Sidén and Norwegian Bjarne Melgaard among others. It was an interest that manifested for some years in many Nordic shows and a strong Nordic presence in a new array of growing biennials.

Key to this expansion were both a curiosity about what was beyond the local art community and a strong desire by governmental institutions to invest in an image of Nordic countries as being contemporary and creative; the ideal vehicles for distributing that image internationally were art, music and fashion. There was a double bind in the image, however, as stereotypes emerged of the North as melancholic, romantic, wild and bound to nature. These clichés were reworked with an ironic and critical twist but were still very present at the time in the work of Finnish Esko Männikö as well as Norwegians A K Dolven and Torbjørn Rødland, for example. Today these wild landscapes have been replaced by works such as the microcosms of Danish Tue Greenfort’s bottled bacteria cultures, the detailed cellular drawings of Norwegian Ane Graff or the comparative studies of the sounds of beatboxers and bats by Finnish Jani Ruscica. Nature is definitely no longer a picturesque view of one’s homeland, but an organic system that is depended upon for future survival.

More than a decade later, it is interesting to consider about how the Nordic scene survived the hype. Without intending to give an overview of the current scene, I would like to initiate a conversation that may help reinvent the image of Nordic art through a very subjective selection of young working artists whose practice I see as relevant in this context. The intense international branding of Nordic art in the years following the success of “Nuit Blanche” did indeed leave a hangover of sorts within the art community. The fatigue was not so much from international visibility, but rather the strategic changes within Nordic cultural organizations: from emphasizing transcultural exchange to adopting the language and tools of national branding. Additionally, the more culturally heterogeneous and geographically mobile art scenes of the North made the established national or regional definitions of art limited and irrelevant. It is for example symptomatic that the Momentum Biennial in Moss, Norway, has transformed from being a strictly Nordic affair to a more openly defined international art event. Today the majority of established Nordic artists do have galleries outside their country, and quite a few of them live outside the North — most favor Berlin. Furthermore, many Nordic artists have received their education abroad, and some never return to their local scenes upon graduation. Swedish artist Nina Canell, for example, whose process-based, alchemistic installations have attained international recognition, is relatively unknown in her home country. Clearly the current identity and definition of contemporary Nordic art is in a state of flux.

The unity of the art scenes in the North and the image of Nordic art have been affected by cultural and political changes both inside and outside the region. The Nordic countries have ties to the European community and have been impacted by the current recession and cuts in cultural funding. Many artists address the loss of the ideal of welfare state utopias and their participation in the global traffic of goods, labor, images and ideas. Laura Horelli exemplifies the strength and criticality of the Finnish school of filmmaking in works that comment on transnational routes for human beings and merchandise. Norwegian Gardar Eide Einarsson cuts and pastes from a global stream of images and signs, making paintings and sculptures that comment on systems of power and violence. The critical and sophisticated work of the Swedish duo Goldin+Senneby plays with the fluid character of owner- and authorship in our contemporary society of downloading, sampling, outsourcing and offshore trading. Constantly shifting in form, exploring performance, lectures, novels and installation, their work playfully avoids all categorization. The shifting value and significance of the symbols and slogans in our commodified contemporary public space is also a recurring motive in Swedish Gunilla Klingberg’s ornamental works that make use of everyday materials. Recycling as an artistic strategy is also vital in the work of Norwegian Marte Eknæs. She uses evocative materials and objects in her seemingly formalistic sculptures. Stripped of their original function, the reused objects emit an uncanny aura of familiarity yet strangeness.

The history of Nordic identity often appears in the discourse of current art production through a seemingly anthropological method colored by a poetic sensitivity. In several of her works, Nanna Debois Buhl has traced the forgotten colonial history of Denmark using film, drawings, text and sound to track the circulation of animals and plants. Vietnamese-Danish Danh Vo investigates the political and historical tensions of our personal histories by altering and combining found objects. His engagement with identity and nationality in art during the mid ’90s was characterized by irony and a sense of fun; the tone is now considerably darker. Argentinian-Swedish Runo Lagomarsino’s series of subtle collages, drawings projections and films map out the connections between the geopolitics of the past to the present. Finnish artist Otto Karvonen has shown birdhouses modeled after European centers for asylum seekers as a rejoinder to nationalism in current political debate. In Denmark, the artist group Superflex has pasted the city with posters in their signature orange color: “Foreigners, please don’t leave us alone with the Danes!”

Swedish Lina Selander’s work revisits the history of visuality. She often works with montages of different image sources. For her latest work she has explored an area close to Chernobyl using Russian avant-garde film, documentary footage and scientific photographs. Her work’s critique of the visual culture of modernity and modernism is strongly emblematic of contemporary Nordic art. It is an investigation of our recent history that often carries a reflection on the utopian aspirations of the modern project in Scandinavia and how that history is reconsidered today. The Danish artist Kasper Akhøj has studied the history of icons of modernism through a series of photographic and installation works. Modernist methodologies echo through the art of Kirstine Roepstorff, who works mainly with collage and montage. Her monumental work Stille Teater (2008), a large theater installation without actors, examines early modernism’s radical aspirations.

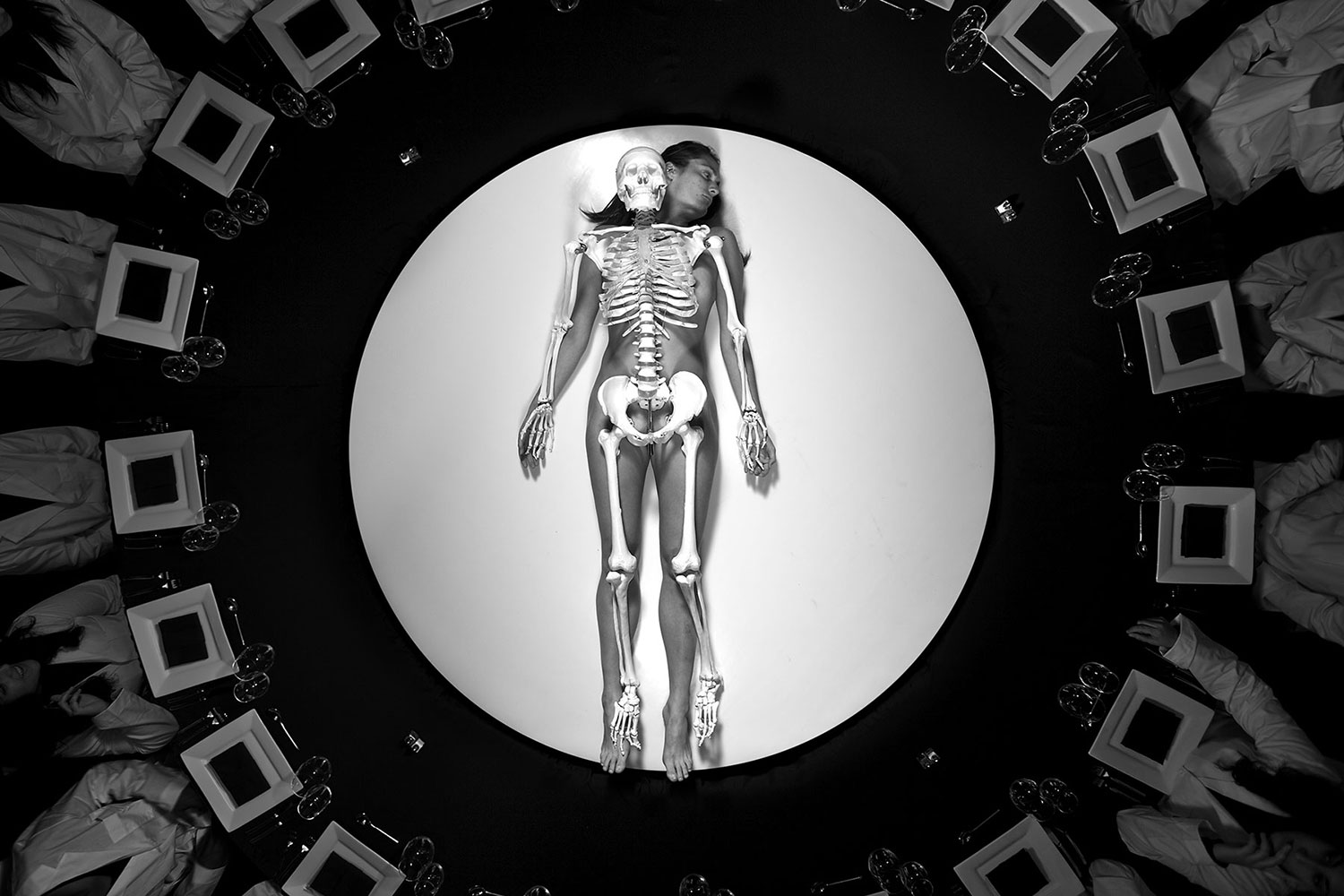

Swedish artist Anna Odell was taken to a psychiatric clinic after pretending to try to commit suicide by attempting to jump from a bridge. Her subsequent confession that her madness was a performance led her to be taken to court, where she was charged with misuse of common resources. Her motivation was social critique, which was certainly achieved by generating heated discussions about the boundaries of art as well as the status of the health care system in Scandinavia — these debates resounded through mainstream media to parliament. Performance in its most expanded sense has a strong presence in current Nordic art, often skirting the borders of dance and sound art but also painting and installation. In the performances and films of Icelandic artist Ragnar Kjartansson, the different personas of masculinity are tested in his humorous yet melancholic art. Compatriot Gabriela Friðriksdóttir reuses mythic tales of Iceland in mesmerizing ritualistic performances that speak of the primal layers of human life. In her work the props do double duty as sculptures. They bear witness to the magic energy of the event that took place. The shift from act to object, from performance to image, is also an aspect of Swedish Ylva Ogland’s enticingly secretive art. Her alter ego “Snöfrid” is revealed through a variety of media including painting, performance, sculpture, film and installation. Performance’s influence on contemporary painting is also visible in Norwegian Ida Ekblad’s expressive works that playfully quote art history. Her paintings and sculptures are inspired by, and used as part of, the music performances of Nils Bech, her close collaborator.

Other shifts in European cultural policy have also touched the Nordic countries to varying degrees. Culture is increasingly valued from the perspective that support to the arts is given in order to influence economical growth in society at large. The dominance of state funding has shifted to a more pluralistic situation wherein privately founded art institutions have taken on a new role, at least in Norway and Sweden. Conditions for art and education have been altered by artist-run structures for sharing knowledge. One example among others is the artist group Parallel Action that arranges seminars and lectures as a part of their artistic project. Norway is also the base for the new Nordic online magazine Kunstkritikk, which has become a strong voice for art criticism within the region but is gaining an international audience. Perhaps this open editorial network for discussion and exchange of knowledge about Nordic art will serve as starting point as we try to move beyond the limiting and reductive frame of national branding.