Alejandra Aguado: I would like to begin by asking you about the relationship of your work to literature. It is not something that appears explicitly in your pieces, but very often you have referred to authors like Nathaniel Hawthorne or Jorge Luis Borges, discussing them as a way of offering insight into your artworks. These are always references to short stories — a genre that I find particularly close to your practice. I think your work achieves an effect similar to that experienced when reading fantastic literature, stories by Argentine writer Julio Cortázar for example, where, almost without noticing how and without explanation, reality — or the world as we know it — is suddenly disrupted by strange phenomena. Although these changes are presented to us very naturally, they still fracture the way in which we understand the world.

Jorge Macchi: I haven’t read Cortázar for many years now, but I understand the link you are talking about. What I particularly liked about his stories is their capability to suddenly turn the most ordinary into something unnatural and almost torture-like; or something normal into something strange through the simple act of observation or close consideration. I particularly remember a short story entitled Instrucciones para subir una escalera [Instructions on how to climb a staircase] in which everything happens very smoothly, but as the story begins to focus on what it takes to go up the stairs — when the attention is placed on that simple mechanical action — it becomes complicated, almost a nightmare. I still remember the feeling of unease and frustration these stories provoked in me. The same happened to me with Borges. Very similar things occur in his stories, but he is more encyclopedic than Cortázar and has all the references to the labyrinth, doubling and nonsense that interest me.

AA: There is another somehow literary activity that plays an important role in your work: journalism. Chronicles, newspaper headlines or pages emptied of words have often become the primary material of pieces such as Doppelgänger (2005), where you have constructed a number of images evoking Rorschach test inkblots with newspaper articles, which share phrases such as “lifeless body,” “abundant blood” or “macabre discovery,” and have used those journalistic set phrases as the link between the doubled image. Other important works having used newspapers are Incidental Music (1997) and Speakers’ Corner (2002), or pieces such as Monoblock (2003), where the pages of funerary ads, now with no text, have become the image of gray, concrete, lifeless buildings through a simple compositional arrangement. Could you tell me what it is about this genre that inspires you?

JM: I don’t know whether to call this literature, as it is exactly the fact that they are not literary texts that attracts my attention — that is what allows me to produce something poetic. The same happens with those other ordinary things I use in my work, such as the image of cars passing by on the street, shoe marks or maps. The spark appears when you use those ordinary elements in the realm of visual poetry or music. It would be completely different if I used a poetic text as a departure point: it would almost be sickly sweet. Those informative texts or everyday things help draw a limit.

AA: Your work has been classified, on many occasions, as neo-conceptual. Nevertheless, you mentioned to me that your works often result from drawings or purely visual experiences and not from ‘ideas.’ You could even say that many of your artworks have a strong surreal quality, which places them in direct opposition to strict conceptual artworks. How do you see this categorization? Could you tell me how the process of conceiving your works takes place?

JM: I am absolutely against these categorizations because they make you see the work with an already established limit. You approach works of art with preconceptions and prejudices. The problem with this is that you miss what the work has to offer visually, which for me is the most important element. What I desire for the spectators of my work is that their ideas come after they have looked at it, after they have experienced it. As far as neo-conceptualism and those terms are concerned, I believe they simplify the works, especially because current practices result from infinite influences and inspirations.

AA: And with regards to the way the creative act takes place?

JM: Most of my pieces come from images that appear in my head, in my eye, from illuminations that come about in very specific moments and to which I feel I have to give some kind of shape on a piece of paper. The first step is then to create a simple drawing and probably afterwards that becomes a watercolor with a bit more elaboration. These help me give form to those images. Nevertheless, at this point the work has also to do with what happens with the media I am using.

AA: Your watercolors have always seemed to me to offer a very good insight into your work, into the strategies that dominate your practice, such as how two completely distinct and distant entities suddenly merge and invade each other. In your installation works this would translate into furniture that seems to dissolve into a mirror, shoe marks that become the image of a firework, or the possibility of feeling there’s water falling down a fountain as a ray of light illuminates a series of plastic bowls. What does this group of works represent to you?

JM: For a long time, my watercolors felt secondary in relation to my other work because I thought of them as a group of surreal images, and that made me not want to show them. Now, what has changed is not my consideration of the watercolors but of Surrealism, which I stopped considering as something that took place in the ’20s and ’30s, and began to understand as a way of thinking and of connecting with the strange. What also interests me about the watercolors is a quality that goes beyond this surreal aspect: it is what happens with the media and with the paint in relation to the paper, what goes on between the colors when they find each other, the way gravity affects the paint. In addition, as my work is quite monochromatic — something that simply results from the fact that the found objects I choose to work with are usually gray, black or brown — this practice allows me to use more colors, or use them in a freer and more enjoyable way. The first time we decided to show watercolors it was for my exhibition at Ruth Benzacar in Buenos Aires in 2002 and I have always included them since then. I do so because I like the way they frame the other work — they facilitate the way I expect the audience to look at my pieces.

AA: References to religion are also abundant in your practice. These appear not only in recent work, such as in La Ascensión [The Ascension] (2005) — the work that represented Argentina in the 51st Venice Biennale, but also very early in your career, when you painted altarpieces where the 3-D effect of architectural views of churches was somehow contradicted by real tools glued to the canvas or wooden support, or by stains of tar, trying to deny the fiction of elevation or depth. In these works, it feels as if you want to bring Christianity’s celestial principles “down to earth.” There is a need for bringing this spiritual realm into the mundane. What is your relationship to religion? What place does it occupy in your practice?

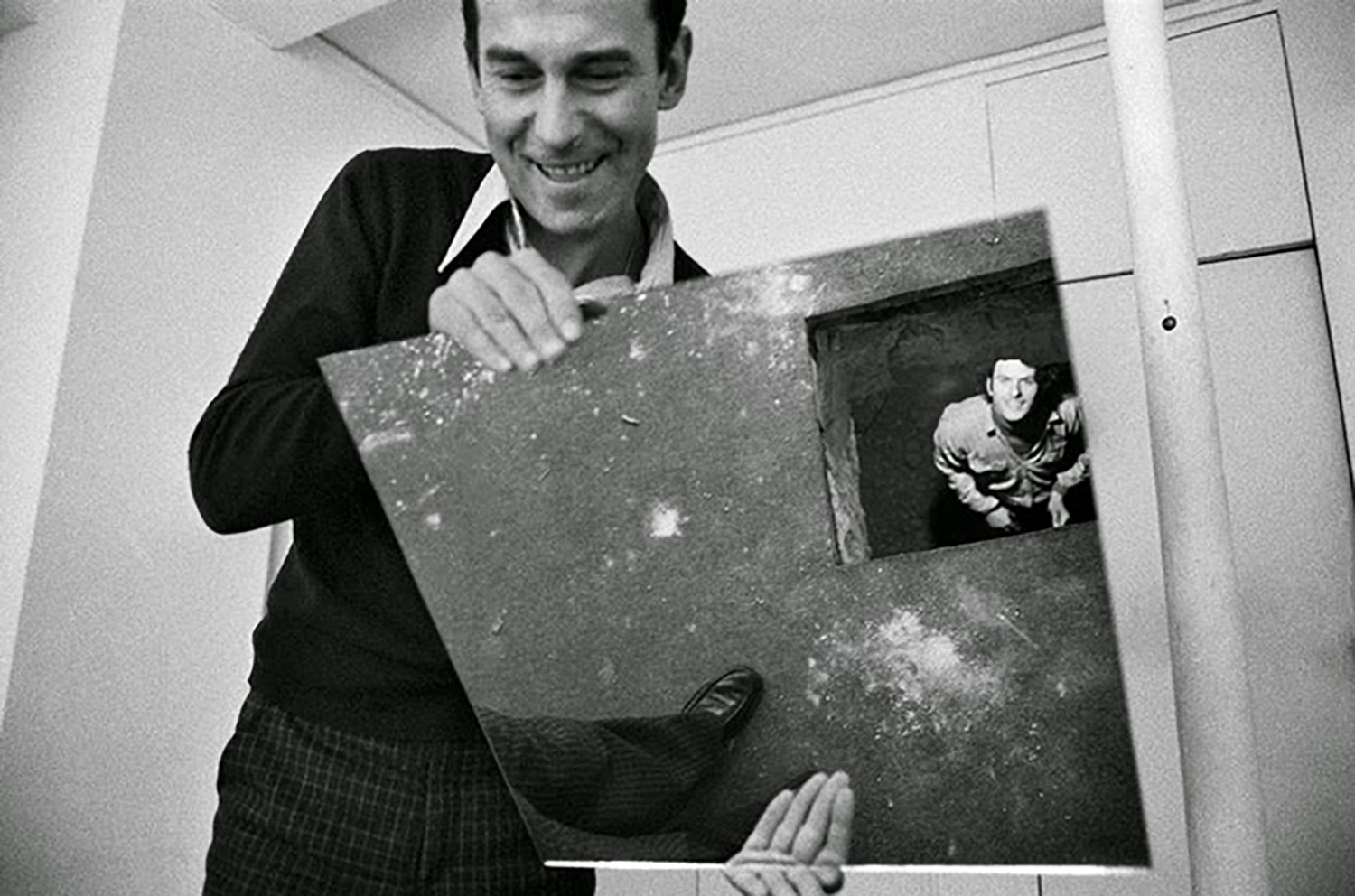

JM: When talking about religion, the two-dimensional/three-dimensional dichotomy is what first comes to my mind. It is actually the central point of the work La Ascensión. This was a site-specific piece at the Old Oratory of San Filippo Neri in Venice.What inspired me was the fresco painted on the ceiling depicting the Virgin ascending to heaven. What we did was place a blue trampoline bed with the exact shape of the fresco (with its curves and counter curves) underneath it, and record a piece of music composed by Edgardo Rudnitzky — performed on the opening night by a viola da gamba player and an acrobat who jumped on the trampoline under Edgardo’s direction. After this initial performance the music and bouncing sound could be heard as part of the installation. On the one hand then you had the 2-D fresco making La Ascensión possible: it was the painting that presented it as a credible situation. On the other, there was the 3-D trampoline bed taking up the space beneath it, and if you bumped into it, it hurt. But this element is what made an elevation actually possible. This was a frustrating elevation because you could only repeat the jump again and again and still come down driven by gravity. This frustration seems to be constantly related to the idea of religion in my work as well as to the idea of the poem, of things that for me always need something real, something banal which I can oppose. This is what happened in my early paintings: there was an illusion that I tried to deny with materials such as tar. I am not sure why I constantly deal with this struggle. I haven’t received religious formation, but my grandmother was a very Catholic Spanish immigrant who couldn’t understand why our parents had decided not to give us that religious education. So whenever she could she took me to the church. And I remember the smell of the candles in these low-lit spaces, the people with what seemed to me weird attitudes, the bleeding Christ, etc. It felt strange to me that this was a space inundated with references to death, but people still went there to heal themselves. I can’t assure this, but my fascination with churches and religion probably comes from these experiences, and I believe this atmosphere of darkness and mystery always finds a way into my work.

AA: You mentioned the word ‘strange’ earlier in the interview. And this is something I wanted to talk to you about, as the word comes up very frequently in conversations with you and in relation to your practice. What does it mean to you?

JM: I like the word. When I can put in words what happens in one of my works, I think that something must be wrong. I hope for each of my pieces to take you to a sort of limbo from which it is not easy to depart or come down. If I had to define art I would probably say it is about generating a feeling of strangeness. And if I had to define strangeness I would say it is something that, for example, happens to me with David Lynch’s films: there’s a point where you feel you can no longer understand what’s going on and you almost decide not to care so that you can absorb all the complexity of what’s taking place.