Rahma Khazam: “Intense Proximity” is the title of the triennial you are curating at Palais de Tokyo and other venues, along with a team of four associate curators (Mélanie Bouteloup, Abdellah Karroum, Emilie Renard and Claire Staebler). What does “Intense Proximity” refer to?

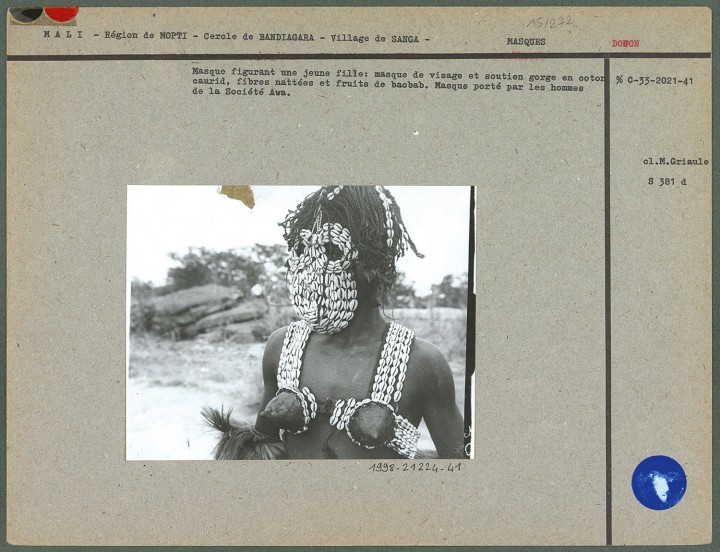

Okwui Enwezor: It refers to our contemporary condition. La Triennale takes as its starting point the work of the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, drawing a line from the research of French ethnographers in the first half of the 20th century to the present, where there are no more exotic peoples to discover and no more faraway places to explore. Instead we have the collapse of distance; we have what we call intense proximity.

RK: The previous editions of the triennial, which used to be called “La Force de l’Art,” focused on the French art scene. In your curatorial statement, however, you stress that you will address global concerns rather than national specificities.

OE: Is it possible to make an exhibition today that is bounded by national frontiers? We come up against a paradox when we try to honor French champions in a great global art city like Paris. The reference to globalization is a way of emphasizing that La Triennale is not an exhibition about the French art scene. It is rather a response to some of the important ideas that have come out of France. These are two very different things.

RK: Will art become increasingly homogeneous as a result of exploring global issues to the exclusion of local preoccupations?

OE: This has been the impulse that has driven the critique of what we call global art: that it’s a form of flattening out, a form of homogenization and lack of distinction between practices, between projects, and so on. But each time this question comes up, it becomes apparent that the rhetoric and the reality are misaligned. Globalization means many things to many people, and because we can’t all quite agree on what precisely it represents, we cannot speak of homogeneity. If you look at our project, you will see that it includes people who were literally born as the 20th century was born, people such as Claude Lévi-Strauss (1908-2009) or Walker Evans (1903-1975), who belonged to the same generation but pursued very different projects. They are no more homogeneous than the young artists we will present, like Camille Henrot or Neil Beloufa, who were born in the ’70s and ’80s. So we are covering a great distance that bridges not only eras but also geopolitical moments, and will help us to make an exhibition that is very diverse.

RK: “Intense Proximity” draws on the work of ethnographers and anthropologists as well as art theorists. How can ethnography have a bearing on art?

OE: “Intense Proximity” deals with the poetics of ethnography, not ethnography itself. Truthfully, I undertook to curate La Triennale not only because of the challenge it represented but also because it was an opportunity to reread Claude Lévi-Strauss’s masterpiece of travel literature Tristes tropiques (1955). Arjun Appadurai’s book Fear of Small Numbers (2006), showing that ethnography is a way of looking but also of being looked at, is also part of this poetics. It shows that within the boundaries of ethnography, we have what I would call constant co-discovery, and not just discovery. As for the relationship between art and ethnography, Hal Foster wrote a very important essay several years ago called “The Artist as Ethnographer” that addressed the concern of contemporary artists with the cultural and ethnic other.

RK: How will you and your co-curators highlight this ethnographic turn at La Triennale?

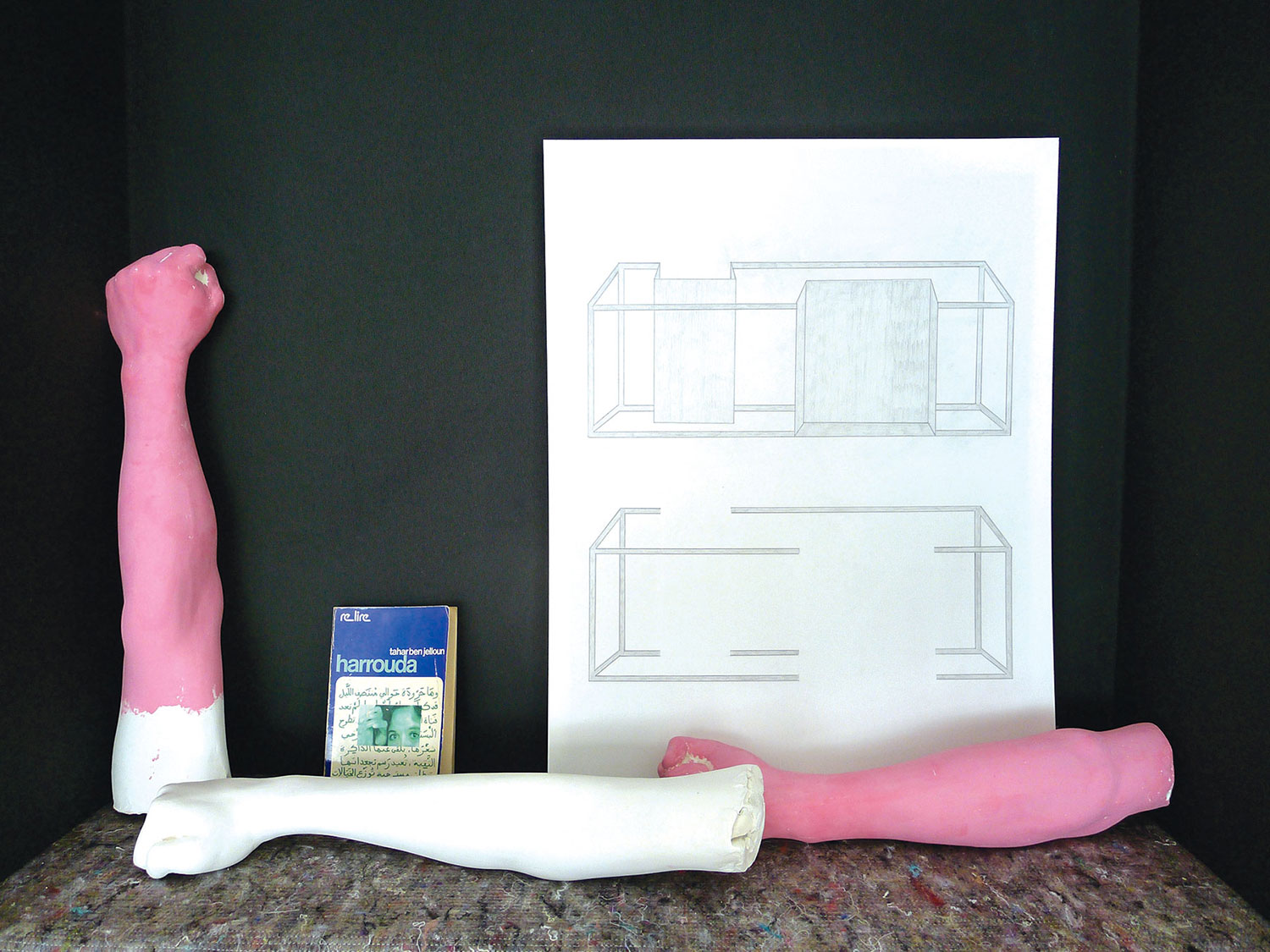

Claire Staebler: We have been identifying and building up different threads, such as the question of self-ethnography — the way artists have been rewriting their personal history, their small history inside the big history. Certain artists from Serbia and other Eastern European countries, for instance, have gone away to study and then returned home to take a fresh look at their legacy and the different ways in which it could be perceived.

RK: You have stated that you want to involve French thinkers and intellectuals in La Triennale. How do you see their role? Will they provide legitimization for artistic experimentation, as generally seems to be the case when philosophers participate in art events?

OE: I really disagree with that argument. The fields of speculation in which artists are often involved are just as complex as those of philosophers. The theorists we will invite to participate in our guest program will not legitimate anything, but rather help to make the ideas underlying the exhibition more explicit.

RK: In your writings you have explored the subject of modernity. Where does La Triennale stand in this regard?

OE: I would say our position is really engaged in the protocol of modernity in that its starting point is modern thought in the first half of the 20th century. But like globalization, modernity is a word that means many different things. In the ’80s we went through a moment characterized as anti-modern, which, because of the resistant impulses located within those practices, can also be considered as very modern. And what could be more modern than radicalism (which in some cases could also be called fundamentalism)? So I think the problem is really that the lexicon of modernity engenders ambiguities when we try to be explicit about what it means.

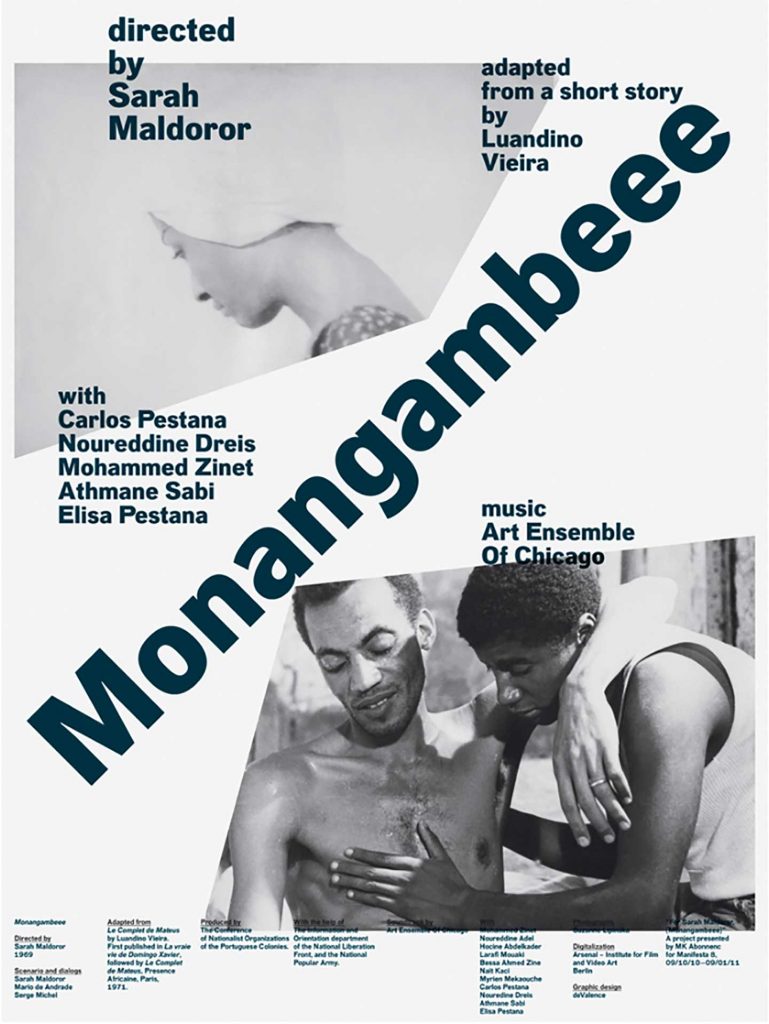

RK: You have also addressed such issues as the status of archival art, postcolonialism, the underrepresentation of African art. Will there be a focus on any of these questions at La Triennale?

OE: No, there’s no one area we are foregrounding. But if you go back to the work Claire talked about, where people are reconstituting their own histories in terms of self-ethnography, you can relate that to forms of archival reconstruction without necessarily specifying the archive as such. But it is there, and it is also one level of our attempt to address modernity, i.e. through self-categorization and the question of taxonomies. Other prominent threads in the exhibition will be the recurrence of the ethnographic leitmotif, the persistence of storytelling, the political climate in which discussions of contemporary art are located — for art no longer takes a distance from events in the world.

RK: This relates to another question you have been exploring: art’s effectiveness as a political gesture. Last July at Haus der Kunst, you moderated a panel discussion on art, dissidence and resistance that examined Ai Weiwei’s imprisonment and the censorship case at the Sharjah Biennial. Will topics such as these come up at La Triennale?

OE: You know that one of the things I found absolutely paradoxical was that the Guggenheim Museum sent out a petition for people to support Ai Weiwei, while they were fighting a petition against themselves in Abu Dhabi! But no, La Triennale will not address these topics.

RK: How do you see the relationship between art and politics? Does art necessarily take sides?

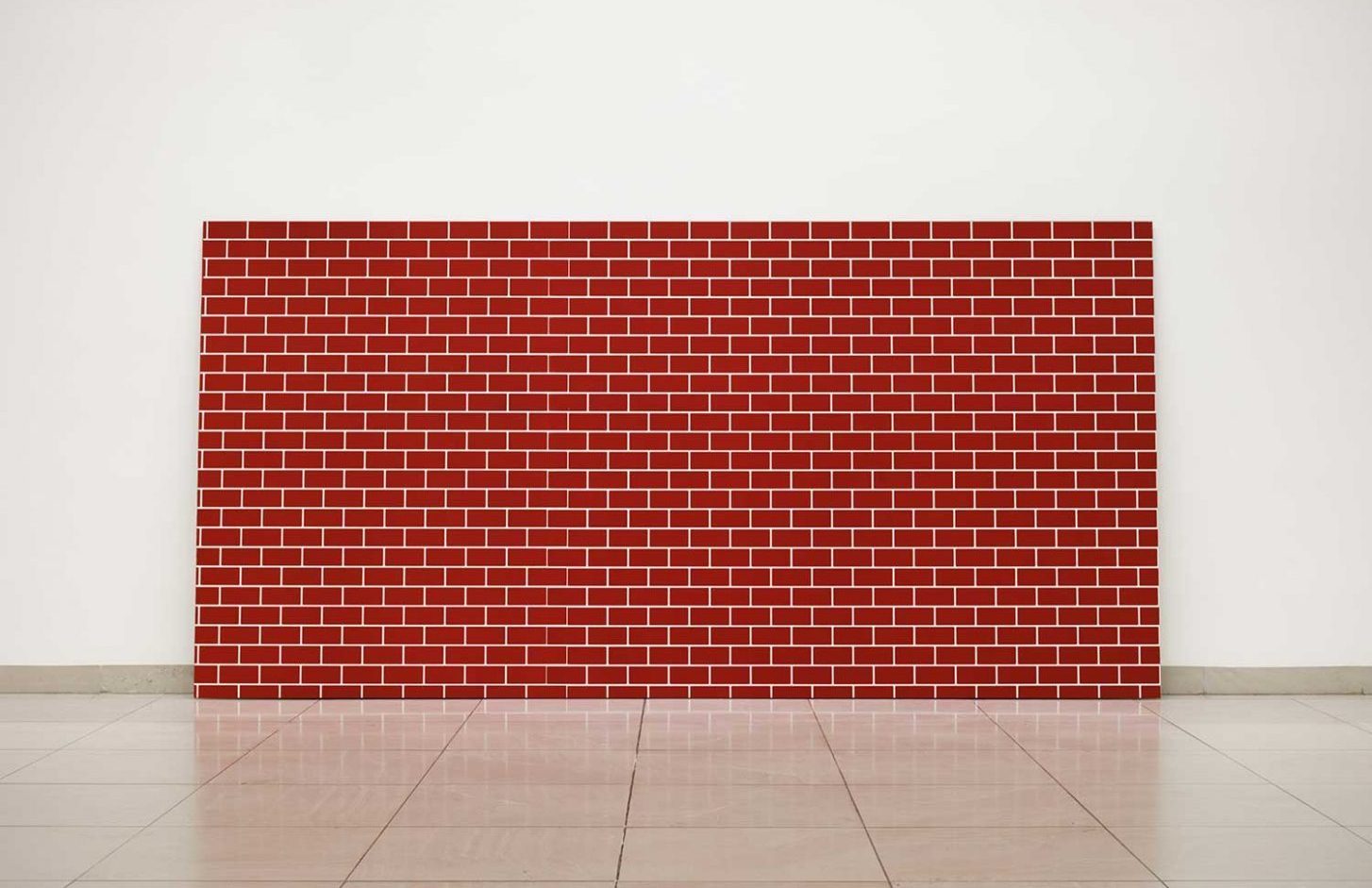

OE: I think if there is a politics art engages with, it is the politics of the imagination. And this is where the so-called autonomy of art comes from — the politics of the imagination and the right to make a proposal, which we can say is interesting or not interesting. That’s one thing. On the other hand, we need to fight against the depoliticization of art, whereby it is considered harmless and the artist is someone who simply steps aside. Walter Benjamin and György Lukács both brought up the question of the relationship of a work to the system of production of its time. Distancing oneself from politics then becomes itself a political position. In other words, a monochrome is not just there to be looked at.

Article originally published in Flash Art #282 January–February 2012.

Rahma Khazam is a writer and critic based in Paris.

Okwui Enwezor (1963-2019) was one of the most important Nigerian and American art critics and curators.