This excerpt is taken from the author’s online book High Entertainment which interprets the myriad destabilizations ushered in by the digital era. High Entertainment proposes a model of cultural production that combines the accessibility of entertainment with the principles of formal discovery and experimentation that have come to define the art context. High Entertainment argues for a new kind of author, described by the term “independent imagination” instead of “artist.”

In media culture, two models of heightened self — “star” and “persona” — consistently play themselves out. The concept of the “star” isn’t very old — 150 years at most, since the time of P.T. Barnum and his creation of modern stardom. The idea of “persona” is thousands of years old.

Both models showcase a performed version of self-hood. Nevertheless, there’s a significant distinction between star and persona. A star’s traits are perceived to be genuine extensions of that person. Julia Roberts the star really is Julia Roberts the person, we think. A star is the whole person — a person blessed with “star quality.” A persona, by contrast, is accepted to be more frankly a construction, an artifice, an invention, an idea on its own terms. Persona is constructed by identifying specific traits of the individual, isolating those traits, and then heightening, magnifying or amplifying them to gain certain effects. Because the star is thought to actually be that person it’s a much trickier concept than persona.

What is a star? The star is not an historical actor — not Alexander the Great, not Nero, not Benjamin Franklin. A star is far less than they were. A star just embodies an abstraction — a congeries of human qualities, heightened, yes, but without being linked to specific historical actions. A star represents only a style of being. “Stardom,” a contrivance, applies a management attitude toward human nature.

The concept of the star has a direct relation to modern media. To project an amplified and magnified self, you need amplifiers and magnifiers. You need machinery — cameras and recorders. The star as we know it is therefore a by-product of the machine age.

A star is a star within a frame of media, and within the industry surrounding and supporting that media. “A star of stage and screen,” “a rock star,” “a star athlete” — there is no such thing as a star without a system. A star is always the star of some cultural system. Star and system are absolutely symbiotic.

Stardom has both production and consumption functions. Culture industries (movies, TV, art, literature, music) need “stars” in order to stabilize the market, predict sales numbers, and reduce risk. Consumers approach the matter with less calculation, singling out certain individuals who, for whatever reason, represent desirable, glamorous or innovative human coordinates. Culture industries are adept at manipulating this response, and (to some degree) controlling it in advance. It is a nearly seamless system. Whitney Houston to Britney Spears to Christina Aguilera to Gwen Stefani, the stars change while the star location remains stable. Maintaining that seamlessness requires, though, heavy audience-response management, i.e. environment control; seeing to it that our affections will be transferred from Whitney to Britney to Christina to Gwen takes a great deal of planning! And as we might expect, there’s a direct relationship between the amount of environment control and the inorganic or inauthentic aspects of our culture.

The idea of the star has hardly changed at all since its invention. Why this stasis? Does the concept of the star simply lack elasticity? Or have our imaginations stalled on this one? Really, the sole profound challenge to the established model of stardom was offered by Andy Warhol, who devised an alternative model based on a radically reductive relation between camera and performer, presented and presenter.

Warhol’s concept of the star came from his insight into a certain technology. Fortunately, technology periodically makes cracks in the control mechanism that are not dependent on one genius’s destabilizing vision. Television famously made a crack in the audience control mechanism long enjoyed by the movie industry. The personal computer made a crack in the audience control mechanism long enjoyed by television. And the digital revolution has produced a very large crack in the entire media control mechanism.

Any High Entertainment aspirant who has a taste for self-presentation might consider the innovation of a new star model — perhaps one in which you’d somehow show the system at the same time that the system showed you. As ever, the form would have to be discovered. Helpful precedents can be identified, though.

Cindy Sherman was still a child when Jane Fonda began exploring her own novel take on the coordinates of self-presentation in a media-saturated culture. Fonda had an insight into the power secreted within the ostensible passivity of the Gazed Upon — did it spring from having cameras regularly trained on her as Hollywood royalty, daughter of actor Henry? — and she then proceeded to organize her life around that insight in a way that broke new ground.

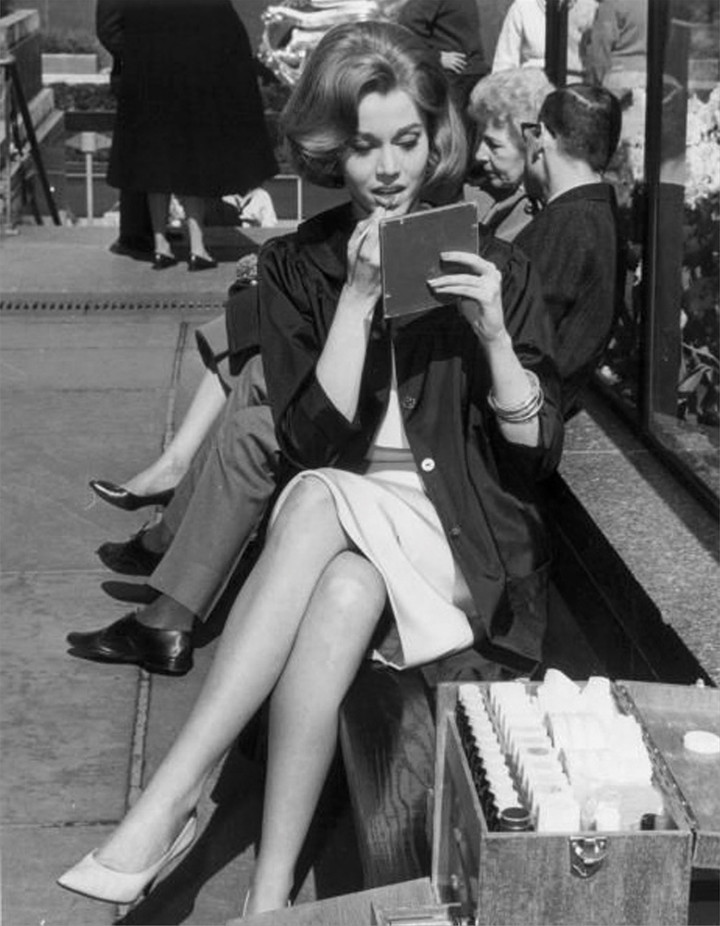

The record of her progress unfolds in a series of photographs taken over many years. (The photographs were not themselves the project but, rather, trace the contour of the project.) None of the photos were taken by her. Some were production stills from movies, some were publicity shots or press photos, others were photo-journalistic documents that appeared in newspapers. Arranged chronologically these images describe a consciousness flowering through a succession of roles.

Jane makes her entrance in the late ’50s as Hollywood Ingénue, fresh-faced find of the movie studios. From there it’s an easy segue to publicity stills that promote Starlet Jane — a Young Working Actress learning her craft but still doing what she is told. Next get an eyeful of Jane working another traditional Hollywood role — Sex Kitten — selling it on the beach, nude, come hither, self-possessed. Va-va-va-voom! Zap! it’s Avant-Garde Jane in her Euro phase as Barbarella, campy sci-fi adventuress, wife of French director Roger Vadim, open to experiment. Returned to American shores, she’s Activist Jane, at a rally with new husband Tom Hayden. Boo, hiss — it’s the reviled Hanoi Jane, visiting the Viet Cong to see the enemy for herself. Lights, camera, action: it’s Movie Star Jane (just as extremist, really, though it reads as a retreat), in ’70s hits like Klute, The China Syndrome, The Electric Horseman, and Nine to Five. Feel the burn with Jane the Workout Queen! Marriage to CNN founder and billionaire Ted Turner lands her another role: Mogul’s Wife.

Hanoi Jane, Mogul’s Wife… Each phase is in quotes. Can she have meant any of them? Did she mean them all? The sets keep changing. Supporting players come and go. Because the subject of the photographs is a famous actress, historical situations and social trends read as theaters — all the world’s a stage, right? Jane, inviting herself into history, absorbs history, makes it hers. Confident that she has your attention, she brings you along on her personal life-adventure. (Imagine the scale of ego involved.) Cindy Sherman would later gain fame for concocting a series of photographic images of female role-playing. But Fonda, while perhaps less clever, was far more radical than Sherman who, bewigged and costumed, carried out her work within the safety of her studio. Switching lifestyle like a change in hairstyle, Fonda did it out there in the world, confident that the cameras would follow.

Fonda worked interesting angles on celebrity, that oh so modern phenomenon which is everywhere shoved at us yet manages to elicit from us only a collective sigh of toleration. For what is the celebrity, really, but a vehicle through which mass media conveys its power and ubiquity? Celebrities are willing dupes of that power — “morally neutral,” Daniel Boorstin called them — and as such they represent a decadence. They accomplish next to nothing in the world of human affairs, yet, because they’ve gained entree to our society’s silly but exclusive VIP lounge, the media culture, expect always to be noticed nevertheless. How to make celebrity interesting? That’s the question confronting the budding High Entertainer who chooses to take the subject on. It won’t be easy: only a few stars (Fonda, Madonna, Michael Jackson, John Lennon and Yoko Ono, Warhol) found ways to use their media access to conceptual, as opposed to a purely commercial, effect. Is there some way to use the space occupied by the celebrity in a more satisfying way?

Some of us have been interested in Paris Hilton for the very reason that she appears to have no other content than the mechanisms of celebrity. Standing before us minus the distractions of apparent talent or ability, she, like the Los Angeles billboard fixture Angelyne, is a concept, of her or someone like her. Other than occasionally mewing “That’s hot!” (her own variant on bland Warholian endorsement), the woman has nothing to say, and yet for some time now she has succeeded in moving from media space to media space to media space, web to print to broadcast. Her “content” is her presence in that space, her access to it, her movement from one medium to another. Movement across the surface of the system that presents her is the only “meaning” Paris Hilton offers. Approve of it or don’t, but hers is a very pure position. That she’s from the upper class is crucial to her contentlessness. An heiress needn’t engage the conventional middle-class success narrative. Neither does she seek change or progress of any sort, as a middle-class person might feel compelled to do. Thus, not only “morally neutral” but refreshingly devoid of the needs associated with most who aspire to a place in media culture, the urge to comment muted, she is able to stand — more accurately, pose — in the foreground as a purer representative of the background. As a result, Hilton functions as a prism through which we observe the disturbing realities of our media system at work.

Whether Hilton is conscious of the concept she embodies isn’t clear. Her inarticulateness frustrates our notions of authorship, and yet the woman is not only making choices but, within the theater that interests her, the correct choices. Clueless she is not, even if the exact amount of her input is unknown. The possibility that the real author of these choices might instead be some manager, talent agent or other behind-the-scenes Svengali is classic show biz opacity, perpetrated a thousand times before. Young Paris may or may not be in charge, may or may not be an artist of the mass media, but isn’t ambiguity of that sort the currency of show biz?

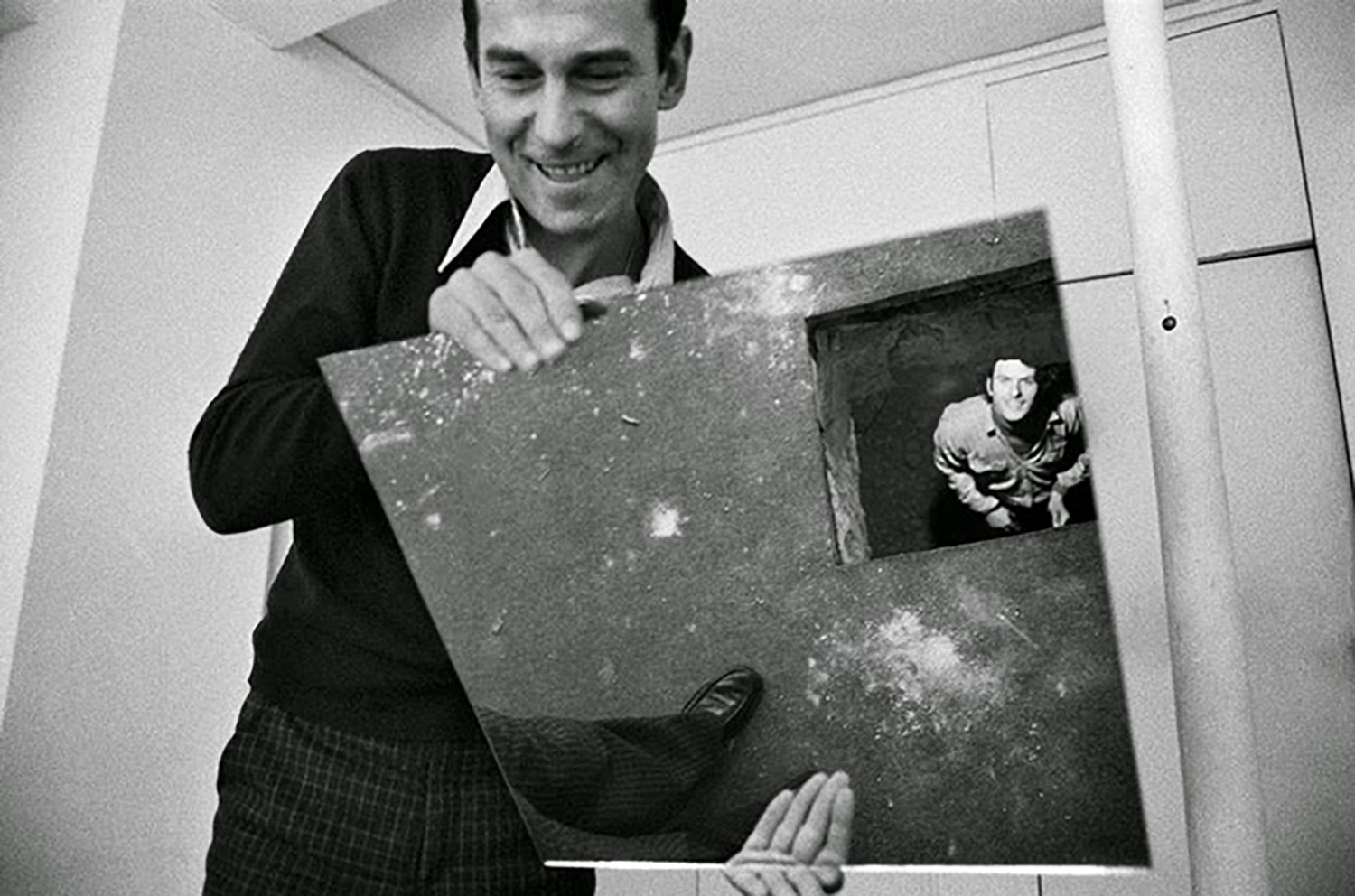

If context isn’t all it certainly determines much: Hilton is considered a joke while her nearest counterpart in the art world, Maurizio Cattelan, is looked upon as a genius. A huge difference between these two does have to be noted up front, of course: Cattelan consistently makes terrific objects that signal his highly sophisticated strategy. He actually does something, in other words. As befits one who’s working in the art context, Cattelan’s intentionality is much more pronounced, much more part of his subject matter — and unquestionably it’s vastly more satisfying to think about a brilliant comedian who is strongly present as the author of his decisions than it is a mere celebrity who may not be. By now the attentive reader will have noticed a pattern. Cindy Sherman represents one kind of sophistication about image-production and role-playing, Jane Fonda another. Paris Hilton can be read as having made a contribution to future work of a sort that Maurizio Cattelan does in a more explicit and directed manner. Ideas useful to the High Entertainer are to be discovered in both contexts. Can we say that entertainers Fonda and Hilton lack all intentionality simply because they don’t foreground it in the manner of artists Sherman and Cattelan? No. Occasionally an “entertainer” will even get to the good idea first! Art and show business are organized around differing cores of transparency and opacity, and the star model will perform differently within each context. The High Entertainer understands this and takes what he needs.