Let us think this thought in its most terrible form: existence (das Dasein) as it is, without meaning or aim, yet recurring inevitably without any finale of nothingness: “the eternal recurrence.”

—Friedrich Nietzsche1

Traversing can, I think, be interpreted in two ways, according to direction: the image traverses the text and changes them; traversed by the image, the text transforms it. Change, transformation, metamorphosis — perhaps hijacking is a better word: the powers of the image captured on the wing, in transit, by some text. Through those powers, examine the nature of the image and its effectiveness.

—Louis Marin2

CHAPTER ONE: SILS

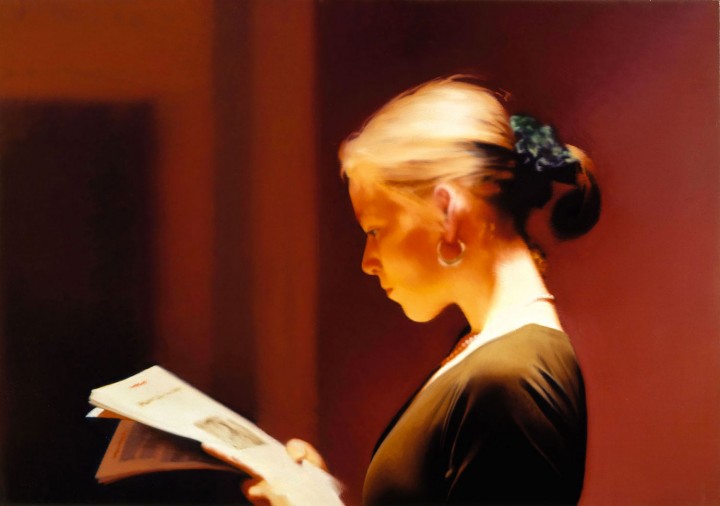

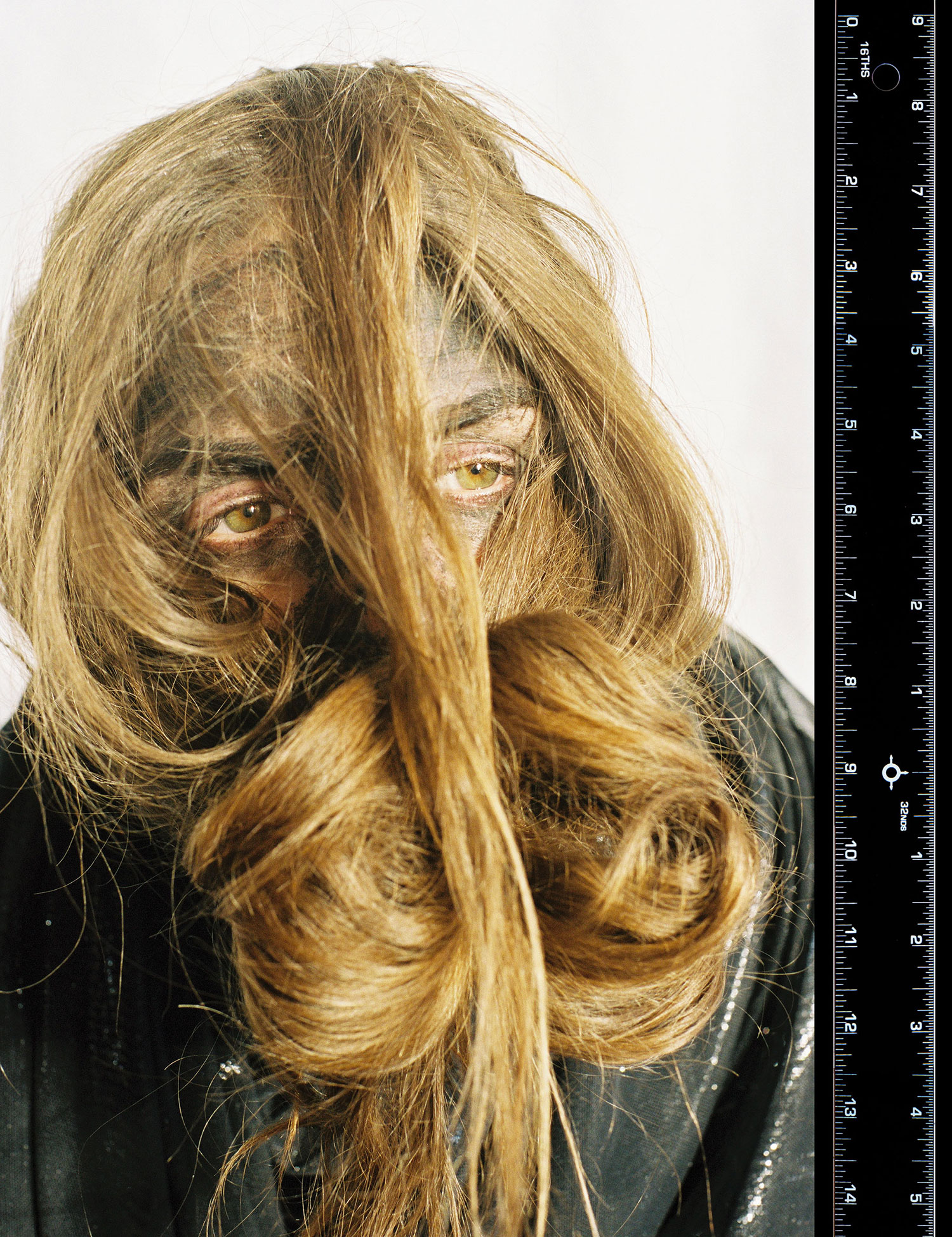

During Gerhard Richter’s regular stays in Sils,3 photos were continuously created and then partially repainted, either becoming part of the collection of works called “Atlas” or, as in the exhibition at the Friedrich Nietzsche House in Sils-Maria, Switzerland (1992-93), shown as autonomous works. In the repainted photos, levels of photographic reality are conjoined to levels of painted reality, whereby the concepts “realistic” (with respect to the photographic level of depiction) and “abstract” (with respect to the nonrepresentational repainting) turn out to be redundant due to the dissolution of categories immanent to painting.

Throughout Gerard Richter’s entire oeuvre, one can find reservations with respect to pictorial formulation, which is absolutely prescribed. Fluid strategies accompanied by doubts about the medium of painting can be seen on the one hand in photographic paintings, in which the picture is shown by using a banal original, and in his abstract paintings on the other hand. In the repainted photos, we see a parallel between these two forms of painterly practice, which refers to the simultaneous existence of contradictory groups of works and series of paintings in Richter’s entire oeuvre. The photographic landscapes appear to be wrong due to the superimposition of paint. Does painting on photography suddenly suggest an unmasked position?

Photography’s pretense of claiming reality is relativized by repainting. Splashes of paint present just as much “reality” as the base upon which they appear. The repainted photos convey ambiguities such as the role of figure relative to background as analyzed by Yve-Alain Bois.4

Whereas the application of splashes of paint makes certain parts of the photographic source look as if it were painted, the paint blends in with parts of the background. An essential aspect of these works is the visualization of general illusion by means of the reversal of the relationship between the figure and the background, which is at the same time in a field of tension with the obviousness of the production process.

The reflection on the genuine and the counterfeit, a quick flare-up of the imaginary trompe l’oeil as well as its immediate unmasking all in one: the eternal recurrence of the impossibility of the painting can be seen as an ostensible overcoming of the impossibility of depiction — Nietzsche’s “Circulus Vitiosus Deus” becomes Circulus vitiosus pictus.

In his book Nietzsche and the Vicious Circle (1969), Pierre Klossowski sees Nietzsche’s revelation of the eternal recurrence, or eternal return, in connection with the fragmentation of the ego from which emerges a potential realization of all possible identities. During these anti-revolutionary moments what is planned and what is unexpected break with the linearity of style.

Klossowski’s interpretation of Nietzsche’s thinking leads from his vision of “the Death of God,” which develops in the creative multiplication of the eternal recurrence to the reproduction of the ego in a differential space, which philosopher Jean Gebser defined as “aperspectival” — an ambivalent space that can be seen in these repainted photographs, for example in the blurring of painting categories. A floating, woven space is presented to the viewer, a space in which the seemingly factual aspect of photography is verified by the means of painting and which exists simultaneously as a painting.

In the practice of Gerard Richter everything is connected and the motifs are confronted with mere motivation, whereby the interaction of two fictitious models meets in the openness of the painting. In fact the light from various painting realities is reflected in the faceted eye of the sphere depicted by Richter in Piz Boval (1992), the subject of which is another work by the artist, a stainless steel sphere with matte finish called Sphere III (1992).

CHAPTER 2: TEXT

For a very long time Gerard Richter was reluctant to publish his own writings. The Daily Practice of Painting5 brought together for the first time the artist’s most important texts and interviews. Spontaneous notes and journal entries appear alongside essays, letters, statements, manifestos, conversations and dialogues produced for specific public occasions.

The themes of Richter’s writings range widely over the intrinsic problems of art. His journal entries characteristically contain reflections on the current practice of painting as well as commentary on the social and political issues of the day. Richter is our contemporary, and his writings are disarmingly clear and direct: now cool and detached, now emotional, now tentative, now bluntly critical. They always go straight to the point. In contrast to Barnett Newman,6 whose major works were preceded by a lengthy period of writing, and in contrast to Hans Hofmann’s didactic impulse,7 Gerard Richter’s writing runs parallel to the act of painting, accompanies it, questions it and is corrected by it. They are concurrent, retrospective and reflective thought processes, in which a high degree of self-reflection keeps doubt alive.

Richter’s energizing contradictions as a painter do not constitute what critics have often unthinkingly sought to hypostatize as the “Richter Style.” His work occupies the point where the originally categorical distinction between photorealism and abstraction dissolves, or at least blurs, into fluid strategies, permeated by the doubts that arise in the practice of painting. Likewise, almost all of his texts work by contraries, as a check on — and exploration of — painting and its premises. Crossovers and contradictions bring certain related basic structures into play, without allowing them to harden into ideology.

Many of Richter’s denunciations of certain forms of contemporary ideology may well seem over-vehement, now that hostility to ideology is often no more than a fashionable pose; but this critique of ideology is deeply rooted in his own experience. Born in Dresden in 1932, he grew up under two dictatorships, and, in the West from 1961 onwards, he took a skeptical view of the influence of any kind of ideology in artistic and intellectual circles. If Richter continually reverts to the subject, this is largely the result of his conviction that there is no escape from ideology through personal experience: one must instead try, un-dogmatically, to translate one’s own passion into reality. In this sense, his statement “I believe in nothing” paradoxically confirms a belief: a free-flowing coincidentia oppositorum, or union of opposites, that transcends the opposition between intuition and reason. Richter’s stylistic and thematic diversity as a painter embodies a consistent and powerful collection of ideas that he has come to express with increasing precision.Like no other contemporary artist, Gerhard Richter addresses possibilities and impossibilities, the function and the autonomy of art today. Without promising direct experience of the object, but also without blindly submitting to the illustrative function of painting, Richter paradoxically succeeds in recovering something like a daily yet critical practice in dealing with the medium. Painting is only one truth surrounded by many other truths; Richter’s works are heterogeneous models, which allow, even demand, perpetual change and mutation.

CHAPTER 3: DETAILS / ARTIST BOOKS

Artist books have become ever more important in Richter’s work over the last years. One of Richter’s artist books I edited is Gerhard Richter. Abstraktes Bild 825-11. 69 Details [Gerhard Richter. Abstract Painting 825-11. 69 Details] (1996), a small-format offset-printed book featuring 69 details of a single abstract painting’s surface, which have been photographed head-on. Needless to say, the painting is entitled precisely Abstract Painting (1995).

At first glance the fragmentary topography leads one to believe that Richter has followed a very specific methodology in order to select these details. A search for fixed coordinates, which are related to regulation as well as to sequence, however, leads nowhere: the non-existence of a system is a system.

Through associative processes, the artist scoured the painting’s surface for interesting spots and selected details from different areas to photograph and record. The individual fragments of the painting became intrinsic elements of the book as they were positioned on whole, single pages with accompanying blank pages next to them, isolating one fragment from another and in so doing creating order from disorder. Surrounding this consequential order are innumerable other possibilities for the creation of order which are worth exploring.

Since the ’60s, the blow-up, or play with scale and the affect of extractions and details have emerged again and again in the work of Richter. An example of this oscillation between micro and macro are the small aquarelles from the ’70s, which shortly after making Richter “translated” into his first large-scale abstract paintings.

Further examples are the two ten-meter-long monumental paintings of single brushstrokes titled respectively Stroke (on Red) (1980) and Stroke (on Blue) (1979) and the sketches of large utopian spaces in “Atlas.” Invited by Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, who taught contemporary art history at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design in Halifax, Canada, in 1977 Richter traveled to the college as a visiting professor and taught for one semester.8 During his time in Halifax, Richter created 128 Photographs of a Picture (1978), a series of photos that, like his previous work, relativized the staid formulation of images by using different views of a single painting — in this case Halifax (1978) — translating them into proportions more suited to photography and books.9

With varying camera angles and the distances between the painting and camera’s lens changing from photograph to photograph, the black and white photographs of Halifax evoke both cityscape and landscape. As the artist zooms through various modes of representation, a comparison can be made to a biologist whose microscope’s focus is in constant flux; as Ingo Rentschler said: “Small receptive fields, finer in their details, are connected to large receptive fields with lower image resolution. The combination of visual information with different ranges of frequency leads to more interesting results than when only one range of frequency is used, as it makes one pay closer attention.”

Pervading Gerhard Richter’s body of work are reservations about the absolute formulation of the image. In the abstract paintings, as well as in the photo paintings where more simple modes of presentation are employed, doubt and failure are manifested. Within the paintings there is a dynamic of self-reflection and articulated tension represented, and this is one of the most integral qualities in Richter’s painting — this enduring ambiguity. Richter’s work occupies that position in which the foundational and categorical difference between realistic (relative to photographic mimesis) and abstract (relative to the otherworldliness of pictures) is solved through fluid strategies — or, at least, they are blurred. The deconstruction and construction of images are simultaneous.