There is a perverse logic in setting up a conversation between old friends Djordje Ozbolt and Subodh Gupta. After staying with Gupta in New Delhi and meeting regularly in different locations around the world, Djordje Ozbolt and Subodh Gupta established a close relationship, though their work couldn’t be more different. The Serbian-born Ozbolt is a fantasist and a provocateur; his paintings recall the posturing of the school joker. His wild combinations of subject matter, titles and bizarre compositions demonstrate a level of conviction and audacity, but behind his self-assured exterior lies a sensitivity towards his subjects. These subjects are as diverse as his family and religion. Once glints of compassion and affection are revealed, the joker’s cover of bravado is blown.

Gupta’s approach is more plain-speaking. He confronts his subjects head-on, opening up a dialogue about everyday life in India, its burgeoning economy and his personal cultural background and rural roots, often through casting or painting familiar domestic objects to create spectacular large-scale works. Both artists refer to their past in their work, but Ozbolt’s influences — growing up in his homeland during the war, his time spent living in India, studying at the Slade School of Fine Art and at the Royal Academy in London and then settling in the city with his family — have led him to confront his subjects in a prolific body of paintings that leap from seemingly unconnected subjects. At the center of this body of work remains, of course, Ozbolt himself.

There are several oblique links between Ozbolt’s and Gupta’s work, mostly related to broad themes: religion, culture, a sense of location (either a rejection of a specific community or the representation of the essence of place and locality). Ozbolt’s work comes together through subconscious and unplanned constructions, with events and incidents finding their way into paintings often alongside pastiches of the artists he is currently looking at. Working serially, Ozbolt tackles his subjects in a seemingly erratic or whimsical fashion. Sometimes the work responds to an event, as in the case of Venice in Spring (2011), which reflects his frustration at not finding a hotel room in Venice. In other cases the work is generated by a simple desire to see an idea or sketch made real. For example, Sunday Best (2010) prompts the question: “What would it look like if a Surrealist painter looked like his painting?” When viewed as parts of a wider picture, these diverse paintings coalesce into an overall practice that is sometimes very detached, sometimes very personal.

There is an enviable playfulness to Ozbolt’s work. The variation of style and format, not to mention his embrace of serious subjects delivered under the cover of light-heartedness, create both gags and complex investigations into cultural stereotypes that cumulatively form a picture of Ozbolt’s absurd understanding of the world.

A recent series references the works of other artists, often informed by punning titles. These absurdist titles mask his genuine affection for painters he clearly reveres. For example, Francis Picabia is spoonerized as Prancis Ficabia (2011); a Giacometti sculpture is resplendent in Rastafarian colors in Jahcometti; and Picasso becomes Koksen (2010), which means “to take cocaine” or “cokehead” in German. Having grown up in Serbia, which has a rich diversity of religious backgrounds, and with a family history of Orthodox Christianity, one subject that recurs constantly is religion. His handling of religious themes is playful rather than critical. For example, in Cleaning for God (2011), a saint clutches a vacuum cleaner adrift in a typically peculiar indefinable landscape. Holding a brush aloft like a sceptre, his are eyes beatifically closed as he does God’s (house)work.

In Pater Familius (2011), a Mujahideen holds a leash around a dog, a sheep and his bodybuilder son. The niche cultures of Afghan and Pakistani bodybuilding bleed into a surreal observation of the family unit. It’s unsurprising that Ozbolt cites de Chirico and the Surrealists as a formative inspiration; in Homeless Saint (2010), the eponymous protagonist pushes his bundled belongings through the countryside in an old shopping trolley; in Guru (2011), a hirsute, comically wizened spiritual guide’s face, colors stream as if his age and wisdom were represented through lines of color. With no overt critique of organized religion, these paintings give the sense that Ozbolt is more generally questioning the reverence usually afforded to figures of authority. His interest is in the idiosyncrasies of human nature and the extremities of belief.

These paintings often position the absurd in stark contrast with order. In a new series of works, titled The General, The Judge, The Ambassador and The Gentlemen (all 2011), aristocratic figures — in robes and uniforms — have their heads replaced with African tribal masks. This may be a joke about inspiration, and a connection to Cubism, considering that African masks — symbols of the West’s fascination with primitivism and exotic culture — were a major Cubist influence.

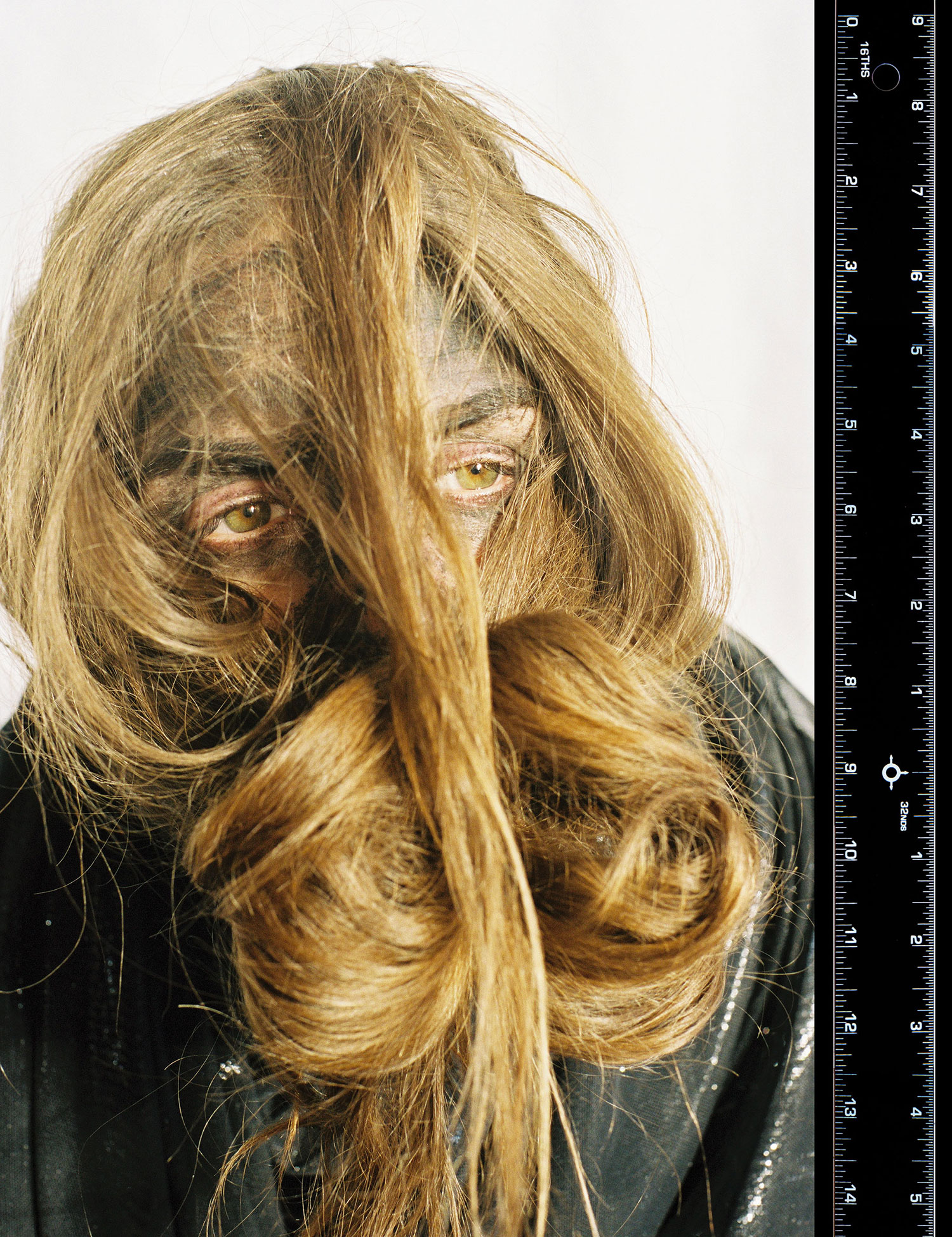

In a series of animal paintings — reminiscent of the work of Giorgio de Chirico’s brother Alberto Savinio — Ozbolt has given each species a wig: a proud-looking pug is bequeathed tumbling brown hair; an iridescent blue bird is granted flowing blonde tresses. These funny, quick-fire paintings become a small part of a bigger picture: a hamburger smokes a cigarette; a bird grasps a plucked eyeball between its teeth. Ozbolt’s overabundant visual language takes elements from cultures in a pick-and-mix way that is surely representative of how we digest culture and information in a digital age.

— Sarah McCrory

Subodh Gupta: You came to London at a very particular time in British art. Perhaps you could tell me a little about how that influenced your work, or your approach to art making.

Djordje Ozbolt: Yes! I moved to London in 1991. Up to that time I was studying architecture in Belgrade and drawing and painting for myself. Arriving in London was amazing in many ways. One of the things was obviously suddenly being able to see all this amazing art. The YBAs were already exhibiting all over London and it was all very new to me. It was a really exciting time. Not only in terms of the art that was that being created but also in terms of the accessibility to it. You really felt that you were witnessing something special. So in many ways the whole art scene in London in the early ’90s did contribute to my decision to study art.

SG: In what way would you say your work is reliant on travel — your being in the UK or the time you have spent in India?

DO: My work is an accumulation of many different things: obviously my varied interests, experiences, education, my background, etc. Travel was always important to me. It was just seeing different places and cultures that opened up different possibilities in terms of making art, especially India, which left a permanent impression on me. I think these impressions get lodged somewhere and then they pop up as references in my paintings.

SG: The Surrealists are clearly an important group of artists for you. Can you tell me a little about your relationship to their work?

DO: My first encounter with art that caught my interest was seeing a book on Surrealism when I was 13 or 14. I was instantly intrigued by their ways of representing the subconscious and the impossible. Quickly I went through most of Surrealism and moved on to the “metaphysical” art of Giorgio de Chirico. For quite a few years he was my favorite painter. It was the atmospheric je ne sais quoi that I really liked. I also liked the way he painted bananas. Coming to London I moved on from Surrealism but I guess their influence is still present in my work.

SG: How does your use of eclectic styles and humor reflect your regard for historical painting?

DO: My use of eclectic style is a representation of my restless nature. I just cannot focus on one style. Although looking back at my work I can see a certain style developing. I get a lot of ideas that are very different from each other in terms of subject matter. I then tend to address that idea with a “style” that I feel is appropriate.

SG: Can you tell me who are the figures you regard as your foremost influences? Perhaps starting with whom I might most be surprised by.

DO: It is quite difficult for me to answer this question specifically as I was influenced by different artists at different times. I tend to look at a lot of painters but I also like artists who have never made a painting in their life. I do look at a lot of historical paintings as well as new ones. I reference a lot of old masters as I have great admiration for some of them. Obvious revered ones and some less known ones whose work often pops up in auction catalogues. I love Picabia, Malevich, Alighiero Boetti among others, but the list would be too long to print.

SG: How do you start and finish your paintings? Do you have an image of the finished work when you begin?

DO: It depends. Sometimes I have no idea what I am about to paint. I quite enjoy painting in this way. I just start and see where the painting will take me. And sometimes I have an idea, which I try to translate into a painting. Mind you they always end up different from the original idea. I like the changes along the way.

SG: There seems to be a narrative abstraction in your work as well as a more formal, or literal, abstraction. Can you talk a little about this?

DO: Again, some works are total abstractions but there aren’t that many of those, and some have an obvious narrative. I try to combine the two if the painting permits. Although my work is mostly figurative I try to play with different elements of the painting. Background is one of the areas where I like to experiment. It’s the process of painting itself that determines the final result.

SG: Can you talk about the scale of your paintings, which recently have been larger than earlier works. Is this shift due to a change of subject, perspective, or related to the paintings as objects in their own right?

DO: There are so many paintings that I have seen hundreds of times in reproductions and never in real life. So I establish a relationship with the piece based on the reproduction and often I am really surprised when I see the piece in the original. At times I had imagined the painting as much larger or smaller than it actually was. This was one of the reasons I started working on different-sized canvases. Early on I used to make smaller-scale paintings, mainly because of practicalities like the cost of stretchers, the size of my studio. Later it just became habit. At one point I decided to try larger paintings and see where it would take me. I was curious if I was going to make the same painting — just larger in scale — or if the scale would change my paintings. This is a process that I am currently still exploring. I realize that not all of my paintings work well on a small scale, and for me it is definitely more challenging to paint big.

SG: You had complete freedom in choosing someone to interview for this piece. Why did you chose me?

DO: We have known each other for a long time in different periods of our life and career. I don’t know — maybe I feel comfortable with that. You are as familiar with my work as I am with yours. And I love you, man!