Much has already been written about the audacity of the New Museum’s inaugural exhibition. As it made its ascension to the higher echelons of the art world with each staggered tier of its swanky new building, it chose to center its first show around the ‘unmonumental,’ thumbing its nose at the hype and hot air so much of the art world feeds on. “Collage: The Unmonumental Picture,” the second installment of the show, complements the sculptures of the first exhibition with works by eleven artists spanning a couple of generations, each body of work imprinted by a singular creativity.

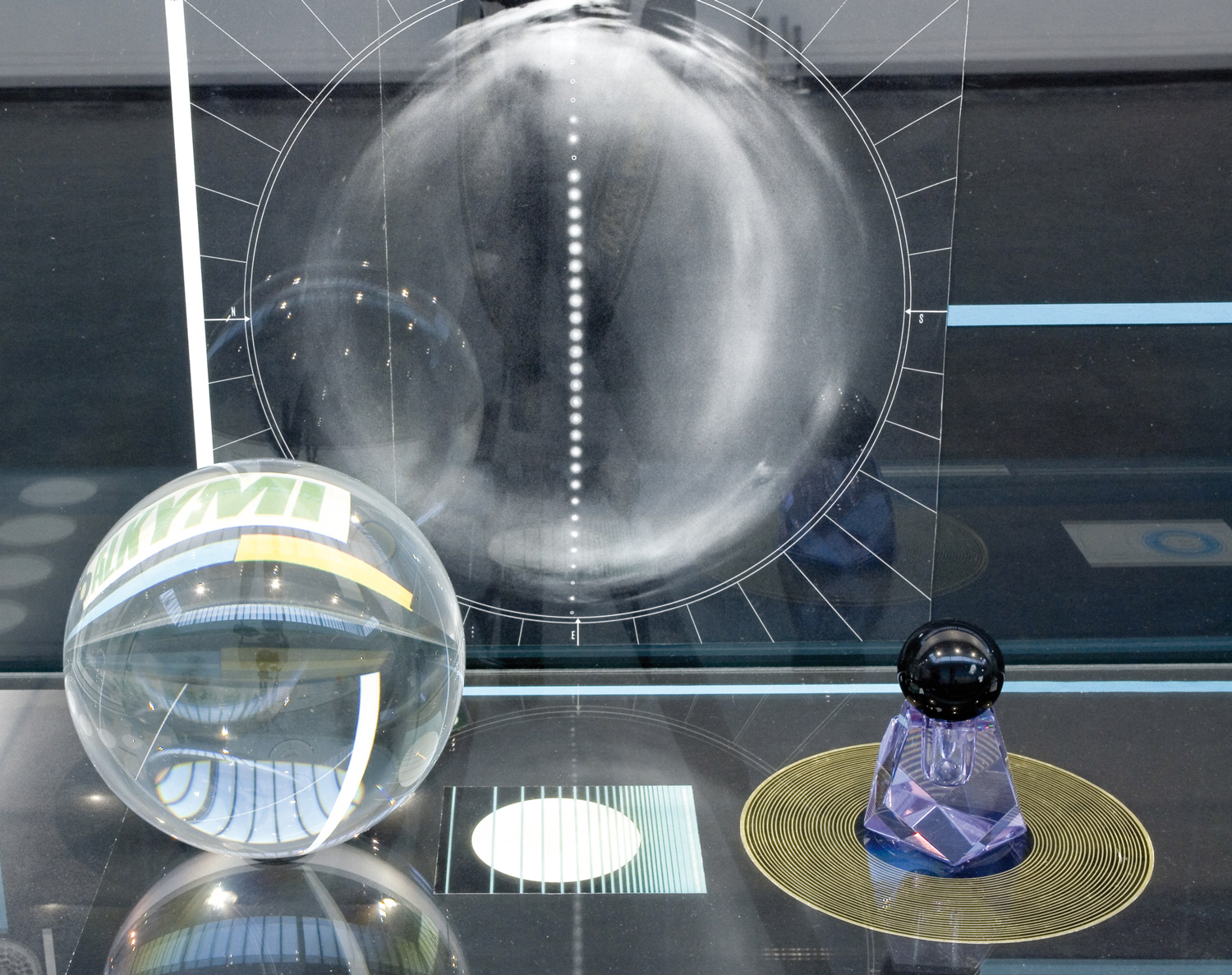

Collage, in its most basic form, an assemblage of different pieces of paper — a rather humble medium to open with — was a natural choice for the New Museum’s curatorial team. Paradoxically, two of the most outstanding works were distinctly ‘monumental.’

Wangechi Mutu’s Perhaps The Moon Will Save Us, an extravaganza of pelts, pearls, cutout pictures and a liberal amount of packing tape, covered an entire wall of the museum, practically overshadowing its neighbors. Christian Holstad’s equally expansive Helter Skelter I and Helter Skelter II delivered a joyful cacophony of textures, overlapping images and cracked paint — an assemblage gleaned from street posters and a wonderful exercise in the art of layering.

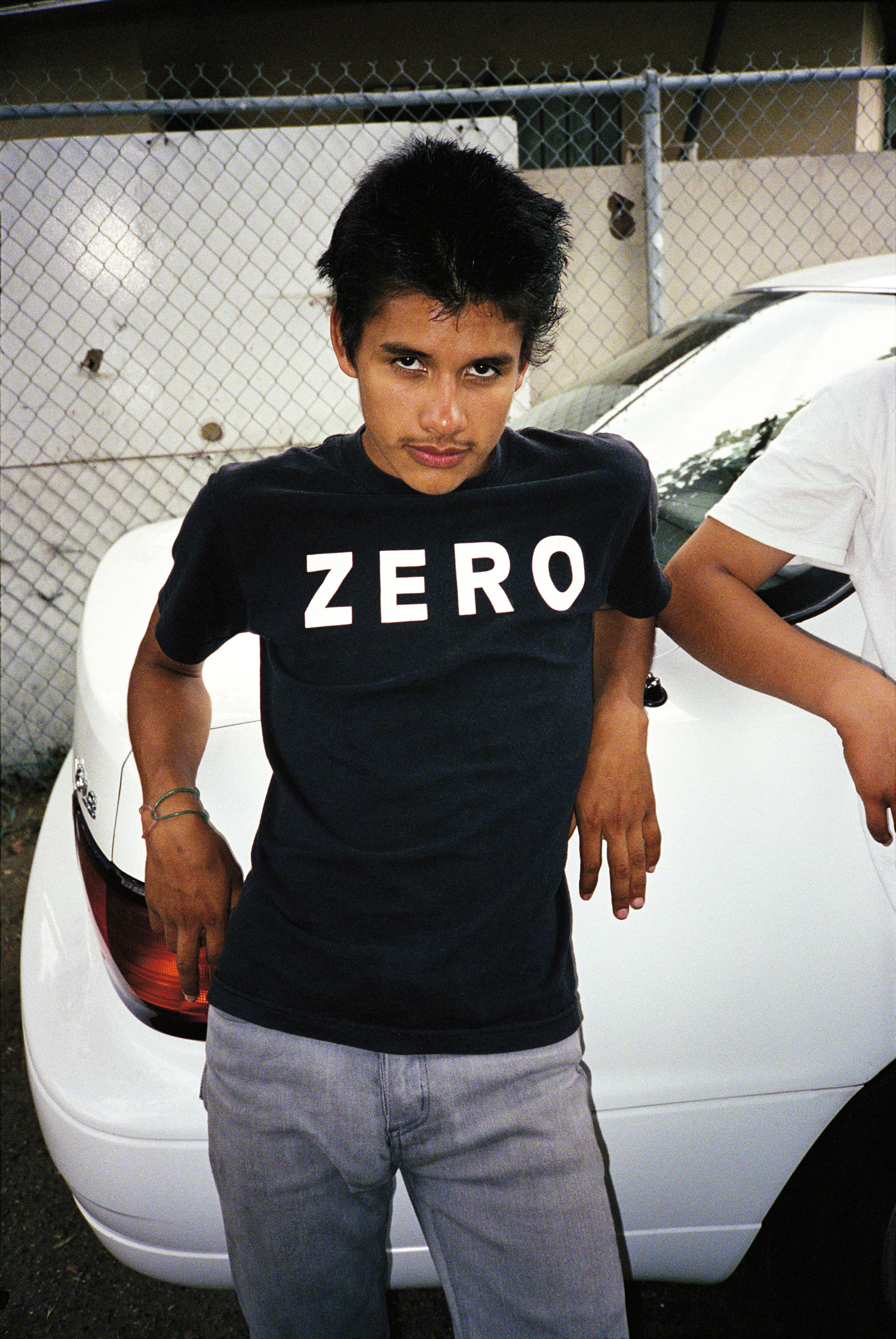

Falling back to more portable formats, John Stezaker demonstrated a mastery of decoupage by doing some clever remodeling of film stars’ features. Also working with photographs, Kim Jones delivered a body of work in which strange bodily contraptions are affixed to photographs of primarily naked men, many of whom seemed to be caked in mud. Henrik Olesen, with Anthologie de l’amour sublime, also toyed with jarring juxtapositions, shattering the quaint gentility of 19th-century bourgeois sceneries with the incongruous addition of a Tom of Finland character here or homoerotic scene there.

Moving on to the realm of the overtly political, Bringing the War Home: House Beautiful is a direct echo of Martha Rosler’s much earlier series of collages on Vietnam, and employs the same strategy of creating incongruous interiors in which images of war and giddy capitalist consumerism clash in a tremor of disquiet. A brunette ecstatically sprays her couch with Febreze amidst the ruins of Saddam’s palace, and Lynndie England, the infamous Abu Ghraib girl, strolls with her leash through a deluxe designer kitchen.

Perhaps even more ferocious is Thomas Hirschhorn’s “Tattoo” series, which exposes the pornography of violence and sex in all of its obscenity. An entire étalage of nipples, splattered brains and sultry bombshells, complemented by an assortment of ideological symbols made for easy consumerism point towards human beings’ most depraved urges.

New beginnings can be daunting, and the temptation to retreat to the safe territory of complacency and crowd pleasers can be strong. Fortunately, and despite its new glamorized image, the New Museum has proved it hasn’t lost any of its bite.