Adam Szymczyk: Dear Cezary, Flash Art wanted me to ask you a couple of questions with the intention of publishing an interview. Would you be willing to answer them?

Cezary Bodzianowski: Shoot.

AS: What are you looking for under the stairs? Or, if you mind me putting it like that, I’ll ask differently: you often hide yourself in your works, literally. What are you trying to hide?

CB: I saw wooden spiral stairs and that made me think of my DNA helix. I decided to improve myself a bit. I don’t feel like I have to hide myself behind this or another façade. Everything is an illusion and pure mirage.

AS: It was said that you once kept a closed lid on the number of photographs and videos documenting your actions. Are the actions more important to you than the documentation, or are these two different worlds?

CB: Yesterday they said nothing remained of my actions, today they say “there’s Cezary” of the videos and the pictures, and tomorrow they’ll say that the pictures and videos are all that has remained of me.

AS: How important is the public’s presence for you, their comments and reactions, the so-called audience participation?

CB: I am present during my actions; people, buildings, trees are present during my actions. I sometimes disappear, the rest remains.

AS: Let’s go back in time. What are your memories of the Warsaw Academy?

CB: The Warsaw Academy was something! As they say, it’s where everything began: there were three of us, then four, then three again, and in the end, there were two.

Completely unhindered studying of art’s secrets: until 4 p.m., painting on a set topic; after 4 p.m., the Studio. Marek Konieczny, night-long discussions; work, work, work. You wanted to live, wanted to drink from this source as much as you could. Then it all came to an end. Our professor was expelled from the Academy for depraving the students (very much like Socrates). And us? Each of us went in his or her own direction. What remained was the dream.

AS: What caused you to move and how do you remember Antwerp?

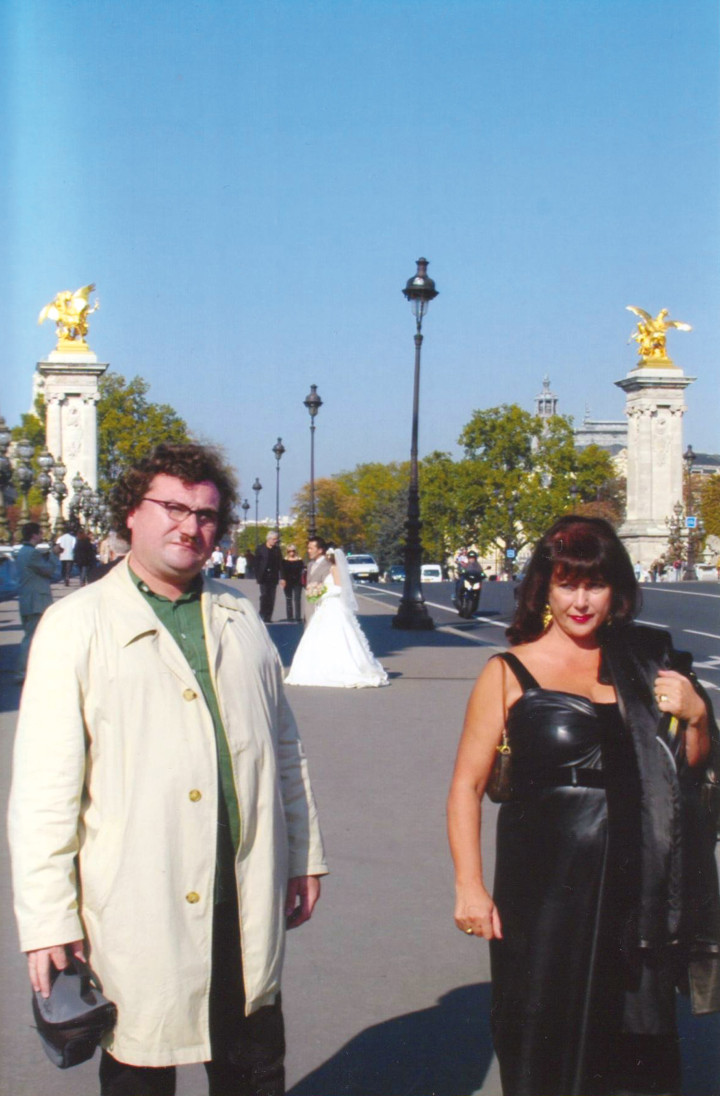

CB: What caused me? I didn’t want to stay in Warsaw after all that. I was afraid I’d be forced to deny everything I had learned. And Monika Chojnicka, my wife, was already in Antwerp. She was the witness of hundreds of events in various places and various circumstances. She also documents all my actions.

And in Antwerp: René Magritte, Paul Delvaux, Marcel Broodthaers. It was a beautiful change: out of the frying pan into ecstatic fire.

The system was similar: until 4 p.m., painting on a set topic, after 4 p.m., working in our mini-studio in the mini-apartment in the loft of the house on Winkelstraat. A lot of objects, performances, videos, photographs — on and on, for four years. Very tough, but wonderful.

AS: What happened with the works you made there?

CB: I made plenty. But because it was impossible for me to take them all with me, I decided to leave the bulk with the landlord. I promised him I’d come the next year and collect everything. The next year it turned out there was nothing to collect. There had been a flood in Antwerp and the basements had been flooded. I guess all my works had gone with the flood! My only consolation is that these works were photographed, that a lot of photographic and video documentation of my work from that period has survived.

AS: I’m sitting with Elena Filipovic, we’ve been talking about you, and she proposes a question about time: time seems an important aspect of your work. You are known to lock people away in an office and walk away. Or you read Kafka’s Castle to them, disrupting their regular workday routine. Do you prefer to give time or take it away?

CB: Even if I take time away from someone, I think I give it back twofold. By sharing this time, I transform it into another value. Just as movement produces heat. Time is an important component, actually an indispensable one, of living and dying. Still, I often work outside time and I find this space very interesting.

AS: A (supplementary) question about space. The perspective of an apartment, a city. How do you feel in open spaces? Are you an urban artist?

CB: A similar case here. Just as space defines precisely every detail and movement that is countable and finite, so you can find a negative of space — an area that keeps expanding, like the universe.

This area, trying to find it, is what fascinates me.

AS: I’d like to return to the question about photographs. Is photography depriving you of your daily bread? What I mean is that the photograph is an object and it attracts attention, which means that less attention is perhaps focused on you…

CB: I don’t think photography will deprive me of my daily bread, just like objects and videos haven’t. The difference is that I’ve never shown photographs before. No, photography won’t deprive me of my daily bread — on the contrary, like videos and objects, it can only give it to me.

AS: What were you doing when, for a recent art fair, you set yourself up in a hotel near a lake while your gallery was at the fair waiting to receive a daily parcel with Polaroids from you?

CB: Montreaux was a nice place, which the pictures show. What was I doing? Boredom, emptiness. Nothing, almost nothing, boredom, emptiness, and an insipid and sleepy view of the lake and mountains from the window.

AS: What artistic strategies do you esteem (a question about your masters)?

CB: One artist I certainly hold in high esteem is Sofonisba Anguissola, the Renaissance woman painter. Her determination and courage are a powerful driving force in my work.

AS: Elena wonders when a performance begins and when it ends for you. Is it necessary that others witness it for it to be a ‘performance’? (If a tree falls in the forest and no one sees it, has it really fallen?)

CB: I’m not sure myself. The performance is probably a sequence of events involving my physical or mental activity. These events trigger one another off, like a domino effect, and I become another link, or I make the first move, and the rest happens by itself, like the poles in Zorba the Greek. The poles have fallen, everyone saw them falling, and yet no one believes it was for real because it’s a movie, it’s fiction.

AS: How do you visualize Berlin?

CB: I don’t have to visualize it because I’ve been there, I’ve seen it, and one day I’ll certainly do something with it — but what? Let it remain my secret for the time being.

AS: Did you ever visit the former GDR?

CB: Never, but I know from Monika that leather shoes and jelly bears were something.

AS: What about West Germany?

CB: Yes, I’ve been to West Germany once. I didn’t spend much time in Berlin, but if you mean the so-called inspiring memories, I still remember the story of Monika’s New Year’s Eve party shortly after the Wall came down and how, the following morning, with her closest friend, they found a Christmas tree on the street, and my wife, always getting soppy about things that are sad, abandoned and uprooted, decided they were taking it with them, so they carried the over two-meter-tall, still-green tree to the bridge and threw it into the Spree so that it was “free and sailed where the waves would take it.”

AS: How will you go about thinking about your contribution to the 5th Berlin Biennial?

CB: Berlin is a changing city, every time it’s different, new buildings, new things to see, I walk around and look for inspiration. My strategy, then, is very similar to the strategy of the city of Berlin. I will prepare some actions or create situations in the city and in the garden at Kunst-Werke, and the documentation of these actions might be on view as part of the 5th Berlin Biennial. But I am also preparing and thinking about a sculpture, which I will try to realize at the outdoor venue of the Biennial. I will bring things from Poland and integrate them into the sculpture.