Donatien Grau: You first established your gallery in Nice.

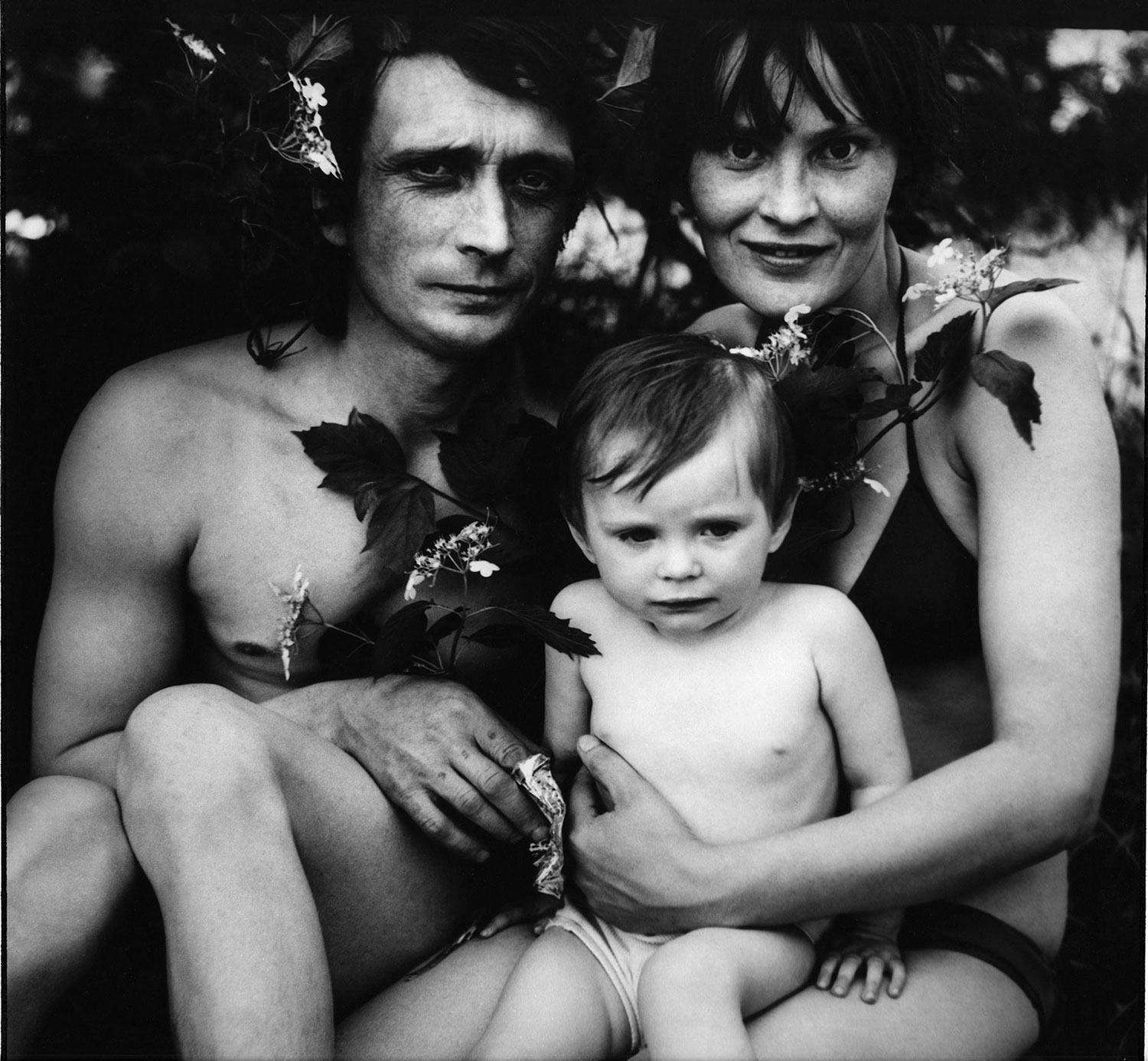

Florence Bonnefous: We first met when we were both students at the École du Magasin in Grenoble. There we became friends with artists such as Philippe Parreno, Philippe Perrin and Pierre Joseph, who were students at the École des Beaux-Arts. We didn’t know we were going to work together, we were just friends. We decided we wouldn’t do it in Paris, so we thought we would rather go to Southern France, where Edouard’s family is from. And we went to Nice. Then, our artist friends joined us there.

DG: That’s where you organized “Les Ateliers du Paradise” your first exhibition in the summer of 1990, which has become some sort of legend.

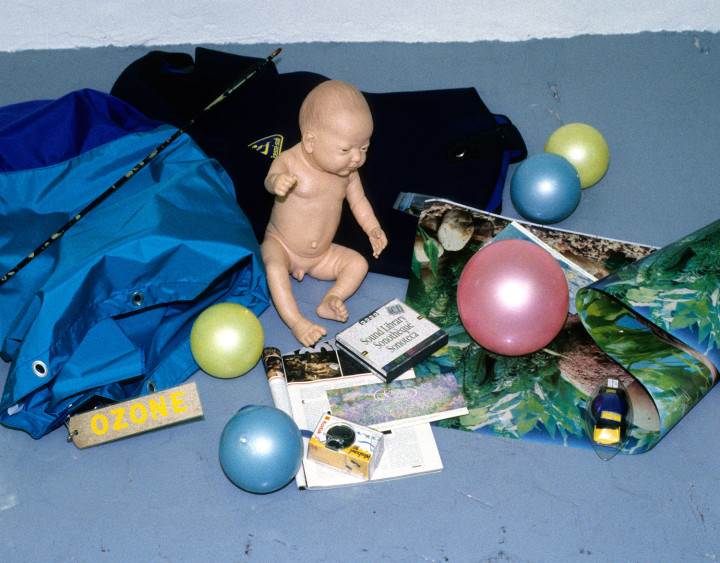

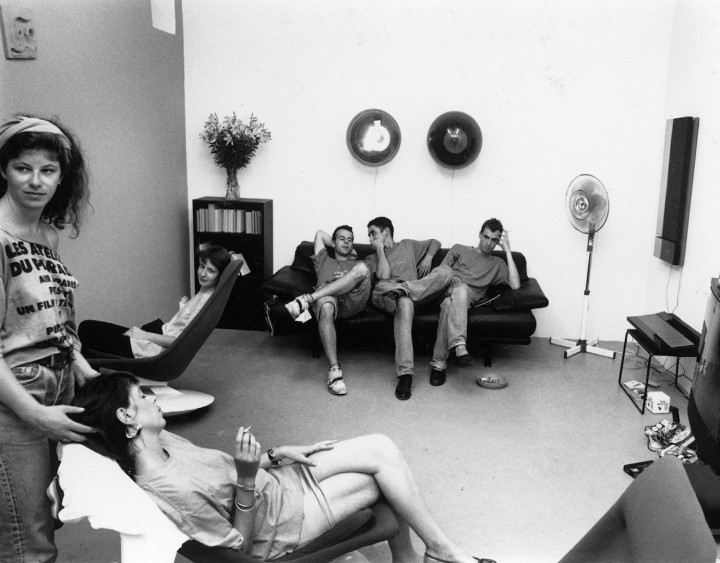

FB: Paradise was the name of a famous nightclub in Monte Carlo. Of course, it was much more than that: Perrin, Parreno and Joseph stayed in the gallery for the whole month of August, and they had given us a wish list of everything they wanted. It was some sort of “Santa Claus list.” Obviously there was quite a difference between what they desired and what we could get. This exhibition was momentum in the definition of relational aesthetics (nonetheless, it was never conceived as such). And then people got together: Nicolas Bourriaud was a friend of Edouard’s, Eric Troncy was a friend of mine. We introduced them to those artists and others came as well: for instance, Carsten Höller, who Edouard had seen an exhibition in Paris.

Edouard Merino: And Liam Gillick, who drove to the exhibition because he had seen the name of it and loved it.

FB: It then became a whole generation: some of us were artists, others were critics, others worked in institutions. For instance, Olivier Chupin, who was the director of the Fonds Régional d’Art Contemporain in Poitou-Charentes, acquired an extraordinary body of works by all these artists.

DG: This whole generation has risen to be quite prominent.

EM: It took time! At the beginning, we were violently criticized. People said we were doing “art for surfers.” Then we left Nice to Paris. Anyway, it’s difficult to run a gallery outside of the center. Artists want to show in Paris and the buyers want to see the works.

FB: Less and less so now: private buyers do, institutions, less often.

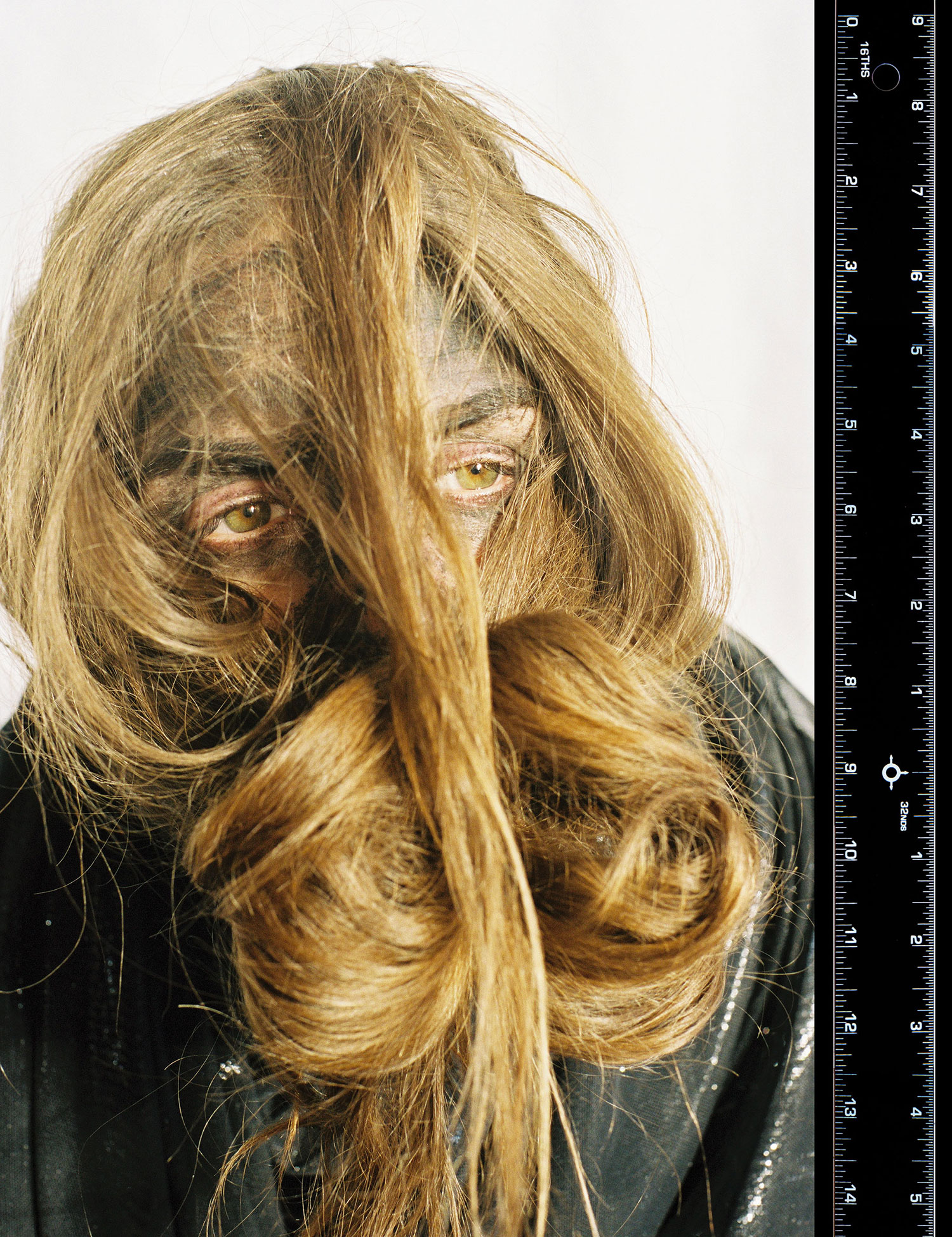

DG: But you still represent artists from Nice, such as Bruno Serralongue or Jean-Luc Verna.

FB: Indeed, in Nice we met another group of artists, who were part of another generation. They had studied at the Villa d’Arson and we started to represent them.

DG: Another important fact about Air de Paris is that you work with prominent American artists such as Raymond Pettibon that you showed in 1991.

FB: We also work with Rob Pruitt, who was in Eric Troncy’s show “No Man’s Time” in 1991 at the Villa d’Arson. We even did a project with Paul McCarthy in 1994. Jean de Loisy had told us that he wasn’t represented then, so I went to Los Angeles, met him, and we became friends. We did a very nice project together; but then we stopped this collaboration for lack of money and space.

DG: And Trisha Donnelly. You did her first international show after the one she did at Casey Kaplan in 2002.

FB: Yes, that’s true. But what’s more fundamental to us is the fact of having collaborations with artists we believe in, no matter whether they sell or not. For instance, one of the artists we deeply believe in is Pierre Joseph. He is deeply admired, especially amongst artists, but he hasn’t yet achieved the international and commercial recognition we think he deserves.

EM: Yes, Pierre Joseph has been, for quite some time, following an intellectual, reflexive path. Some artists know how the system works. They know how to handle things commercially, they have many shows, and that’s good. But we have to be here also for the ones who develop other creative processes.

DG: Something that is really key to the spirit of Air de Paris is also this openness to different kind of projects, don’t you think?

FB: We’ve never thought of it as a strategy though. We did a project with tattoos: I had told Lawrence Weiner that one of his statements would be perfect as a tattoo. And he said that he would agree to it, if I got the tattoo myself. So I did. In 1991, we did this exhibition on tattoos: we asked thirty artists to ask as many artists as they wanted to submit tattoo projects. We got innumerable propositions by Vito Acconci and Richard Prince among others. It’s a form of exhibition we’ve used again since then, by asking artists to invite other artists. In terms of curating and exhibition making, we’ve always preferred to let things go, in order to create surprises. One of our major references is Peter Nadin, who did a show that finished at the very moment when there was no space left for a single more artwork. He has reappeared in the history of the gallery with a performance Ben Kinmont did a tribute to Chris D’Arcangelo, who was close to him.

DG: And there were also things outside the gallery, such as “Project for U.F.O.”

EM: U.F.O. was something we did in Monte Carlo: we commissioned artists to create artworks for a building that could be seen by extraterrestrials. Carsten Höller and Lawrence Weiner were part of it.

FB: Nicolas Trembley once called Air de Paris a “conceptual-trash gallery” and I think he was right.