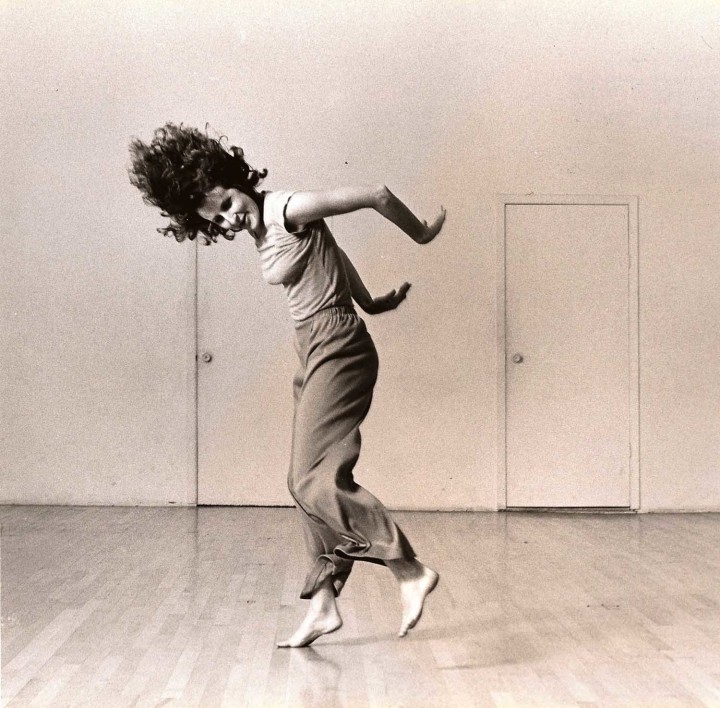

Patrick Steffen: I recently spoke with Simone Forti about the legacy of postmodern dance, and she told me that one of the most tangible influences of that period is related to the quality of your movement, constantly oscillating between gravity and levity.

Trisha Brown: Thank you! What a compliment! This is especially interesting because in the early days my movement was too personal and difficult to teach to others.

PS: Which aspect of Trisha’s work has had the strongest influence on the younger generation of choreographers?

Boris Charmatz: The artists that better understood the importance of her work did not limit themselves to reproducing the typical fluent movements, dancing on a soundtrack by Laurie Anderson [laughs]. The contorted bodies that characterize the work of American choreographer Meg Stuart seem to me to embody a sort of American inheritance, while transposing it into the complex and devastated universe of our society. That said, there is not only one work of Trisha to be considered. The rediscovery of her early choreographies through the project Early Work, for example, is done through modern opera productions.

PS: You spent the summer of 1960 studying improvisation with Anna Halprin, in San Francisco. Her approach toward improvisation was revolutionary.

TB: The workshop with Anna Halprin has been invaluable to me. For instance, sweeping the floor was considered dance. How freeing! Traditional dance was behind me, and I felt that the possibilities were endless. It was there that improvisation really took hold; it’s been a rich and generative process that I’ve continued throughout my career.

PS: You have always pushed the limit of what your dancers could perform on stage. How has your perception of the body changed since the beginning of your career?

TB: The body is a very democratic tool for expression. I rearrange the hierarchy by having a part of the body do what it’s not supposed to do. In the beginning, I was interested in stripping away artifice and projection. Over time I allowed my own personal way of moving to enter the work. It took years of investigation to understand my movement so that I could teach it to others.

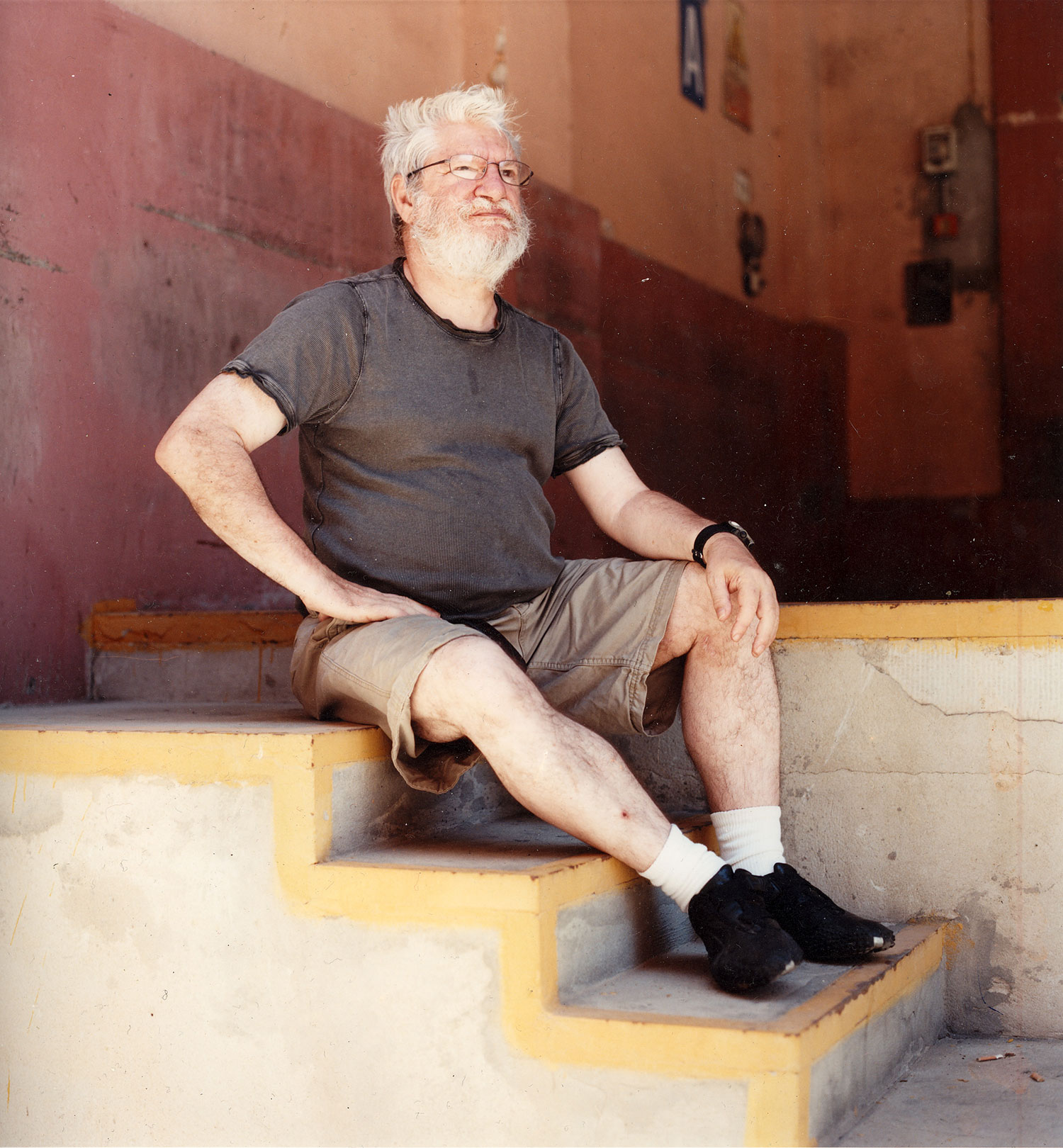

PS: Boris, has your choreographic culture been influenced by Trisha’s work?

BC: I belong to a generation of dancers that have been stunned by the view of Set and Reset (1983) or Astral Convertible (1989), or by a workshop with Lance Gries or Shelley Senter, by the images of the performances on the roofs of New York City, by Trisha’s lectures or the critical texts accumulated since the 1960s. Although my practice as a dancer has been forever marked by these events, my practice as a choreographer has the tendency to oppose what became, following the legacy of Trisha, a doxa of the relâché and the physical availability of the body. Her work is clearly among the ghosts to which we oppose ourselves, for example, in my piece Aatt enen tionon (1996), in which I propose a fairly complicated vision of the body. I don’t want to appear simplistic, but some ideals from the 1960s almost became nightmares for the later artists! When I began dancing, it was almost impossible to explore improvisation without evoking the intense influences of early American experimentations.

PS: I like the idea of ghosts. I remember a workshop with Lisa Nelson; at the end of two intense weeks with precise instructions, the very last improvisation had only one rule: “Don’t fuck around!” And everybody felt so relieved…

BC: Trisha, if you would have the opportunity to visit the Musée de la Danse, what would you like to see? What would you like to do? What would you like to question via this potential museum? What would you fear the most while crossing a public space created by and for dance, using the oxymoron “museum/dance”?

TB: I don’t see the oxymoronic nature of a museum for dance. I’ve been presenting dance in museums for years, and I’m not the only one doing this. But what I would most like to see is a full dance museum. I would love to see it having as many visitors as the Met or MoMA.

PS: Why do we need a museum devoted to dance?

BC: Dance needs a new public space to exceed the separation and the traditional opposition between theaters and schools. The invention of a museum is what appears to be the most adequate solution to create a third space. The apparent antinomy between museum and dance allows dealing with some significant questions concerning unbearable separations: history versus improvisation, legacy versus creation, visual arts versus performing arts, objects versus movement, thoughts versus objects versus corporality, durability versus instantaneity… This project is to be focused on the invention of this museum, rather than collecting memories of the past. It shows the transition from an institutional critic to an institutional construction. This Museum embodies a question, and everyone who has an idea to reply is welcome to be part of it. Furthermore, it allowed us to organize a series of innovative projects. These projects are the foundation of the museum, developing a very pragmatic intellectual working site.

PS: Let’s talk about your project “expo zéro,” a sort of living exhibition, presented at Performa 11.

BC: It was an exhibition where the ideas and the speeches animate the bodies as much as the desire to dance. It somehow belongs to this recent movement. In French, I’d like to define it as tournant discursif (discursive turn), where words play a big role. Trisha, are you interested in this approach? Nowadays, no one is surprised anymore to hear a dancer speaking on a stage! But it seems to me that it is in your performances that we can find the first permission to play with words. Are you always interested in this close connection between voice and body?

TB: I titled my new work from 2011 with a directive I gave in rehearsal. I’ve always had a love of words. I wouldn’t say that I’m always interested in something, but there are many threads running through my work. I pick them up and drop them as my current interests dictate.

BC: While discussing with dancers Eleanor Bauer and Mani Mungai, we had the idea to work with an African team on a version of Set and Reset/Reset (1983), to be called set boum reset. I would be very interested to discover a Kenyan version of Set and Reset/Reset. What would you think about this project?

TB: My company creates Set and Reset/Reset projects all over the world with students and professional companies. It’s an opportunity to learn firsthand the ideas and process behind the creation of the original work from my company members. As part of the process, the students and professional dancers improvise following the original ideas for the choreography. The end result is a combination of my original and their new material. I realize this is different than the kind of appropriation you’re talking about, but it is the only form of appropriation of my work that I support.

BC: Kazuo Ohno, Pina Bausch, Merce Cunningham and Odile Duboc passed away recently. I have often been asked how these events affected me, and I could hardly find an appropriate answer. I do not associate your oeuvre with the notion of death, but I’d like to know what is the relationship between death and movement for you.

TB: Death is not something I think about consciously in the studio unless I’m working on an opera where a character dies. Mostly, I work in abstraction…

PS: Boris, are you concerned with the idea of the transmission of your work? Is it something on your mind while at work in the studio?

BC: I like unusual transmissions. I dream about a dance school by correspondence. I like blackouts, the problem of the transmission and the absence of creation. It is necessary to discuss alternative ways of transmission; otherwise, we will bury ourselves trying to transmit methods of composition and thoughts already formatted.

PS: What happened during the ’80s that somehow shifted the core of dance research towards Europe?

TB: The major change is in funding. These days most artists do not have the funding to support international or even domestic touring of their work.

BC: I’d tend to speak first of all about the economic and social conditions. The Reagan era has to be considered in parallel with the generous financial means that the French socialist government granted to creators, from 1981 onwards. It is sure that the positive support granted to artists in Europe generated a supportive context, despite the immense crisis that threatens nowadays. Thus said, I am an admirer of The Nature Theater in Oklahoma; I improvise with Saul Williams; I presented “expo zéro” in New York with Jim Fletcher, Valda Setterfield, Eleanor Bauer, Heman Chong and Fadi Toufiq. The United States represent something very important to me, even if the current state of programming, namely considering contemporary dance, is not satisfying. But nowadays, there is not a real center for creation; artists circulate enormously, inside Europe as well. We are not anymore here or there; we are here and there.