The turn of the new century has seen Shanghai shake off decades of cultural torpor. Yet the current, widespread image of prosperity hides several infrastructural issues that prevent the city from fully engaging the global art game. In the conversation that follows, Power Station of Art’s director Gong Yan talks with Shanghai “masters” Ding Yi and Xu Zhen. Together they explore the “dark side” of Shanghai’s art system: the dogmatic and platitudinous art-educational methodologies pursued by the city’s schools; the disjointed agendas of private and public institutions; the anomalies of the market; and the stultifying role tradition can play when confronting future realities.

Gong Yan: Xu Zhen, you studied at the Shanghai Arts and Crafts Institute. If my memory serves, you studied advertising design. Ding Yi also studied and then taught there. Did you two have any contact at school? Has design practice or design thought influenced your work?

Xu Zhen: While I was at school, Ding Yi initiated me to contemporary art.

Ding Yi: I studied design at the Arts and Crafts Institute for three years, and then taught there for sixteen years, from 1990 to 2005. My background in design has influenced me in three ways. First, my perspective — looking at things not only in one direction but comprehensively. From the early 1980s, design embraced contemporary culture relatively more easily, and so through design I was able to understand some basic tendencies of contemporary art. Second, the ideas — since design involved an integral form of thinking, when looking at a problem I focused not only on expression and individuality, but even more on reception and acceptance from the audience. Third, the macroscopic view — since design doesn’t focus on only one aspect, design thinking draws you to a more macro level.

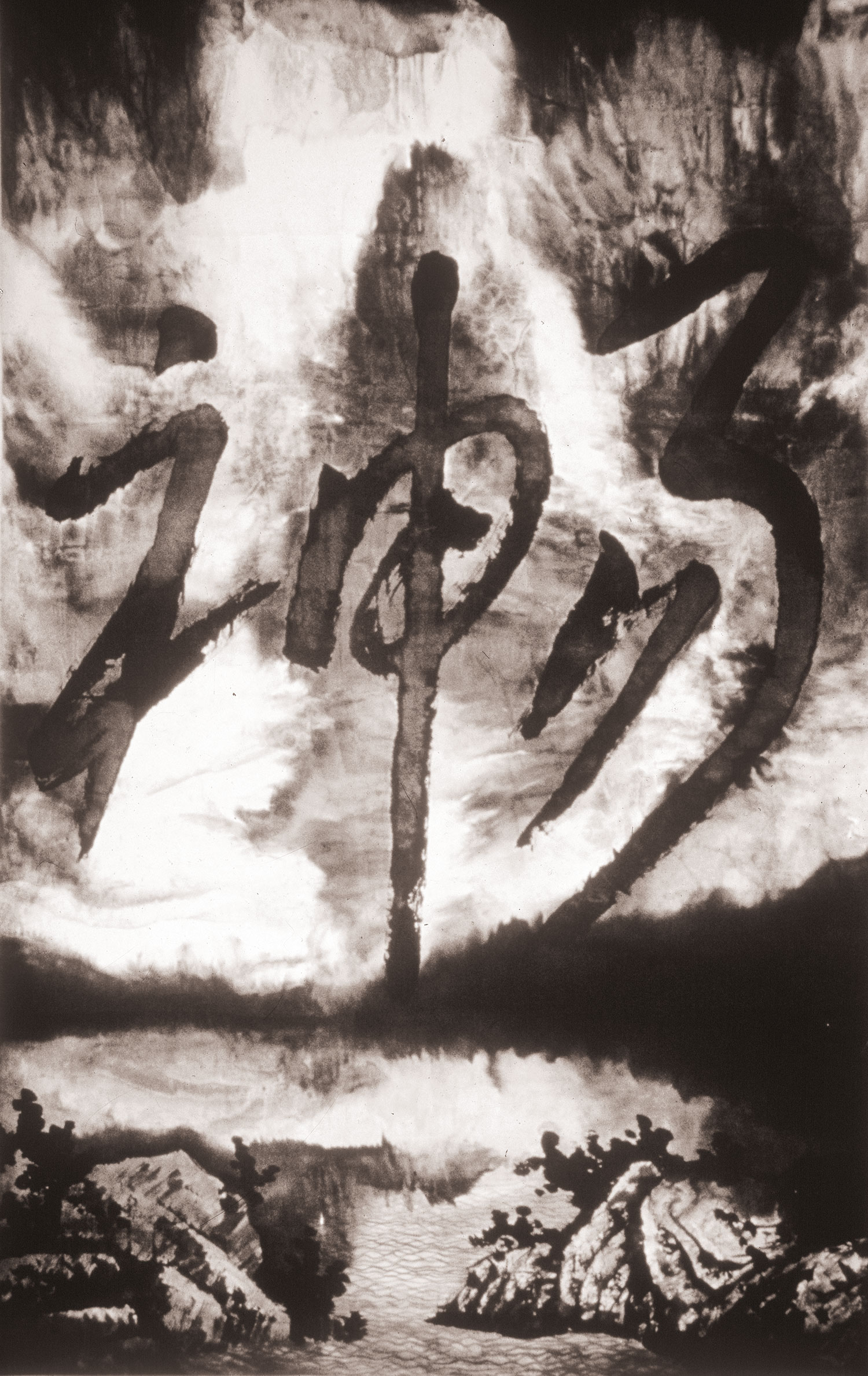

So my design background added another layer to my understanding of art, enabling me to create works like Appearance of Crosses in the 1980s. I wanted to weaken the traditional figurative element, and I felt that if art could be grafted with another field — like design — it would be able to generate something beyond our experience, which could provide contemporary art with a new perspective.

GY: Shanghai is the birthplace of modern art education in China (the Shanghai Academy of Fine Arts was founded in 1912). Yet compared to the stable and enduring growth at the China Academy of Art (CAA) in Hangzhou and the Central Academy of Fine Art (CAFA) in Beijing, what a Shanghai art education once had in terms of being forward-looking and international has vanished completely. This has something to do with historical accident, as well as the aspirations of the city itself. How do you two think contemporary art education in China should develop?

DY: Having worked in education for over twenty years, I think what lags behind most over the thirty years of “Reform and Opening” in China is education. Over and over again, if we were not looking for solutions in the Soviet educational model, then we would look at the European and American ones. We would try to grow more rapidly, or else more systematically. But in the end, we have not gotten back to the basic source of education: training talent. The model of cultivating talent in Chinese education has from start to finish not properly set up a method, so that even today we are still forced to copy different pedagogical systems and ideas. Thus, whether at CAFA or at CAA, or else at the College of Fine Arts of Shanghai University or at the Shanghai Institute of Visual Art (SIVA), our real problem is in fact [about creating] a new system — a system that I think must be contemporary and connected to the greater structures of the age. The art colleges in every part of China face a bottleneck, which is that only students who oppose the academic model can become truly successful. This is worth thinking about.

GY: The Shanghai Arts and Crafts Institute has produced many special artists. Aside from you two, there are Yu Youhan, Qin Yifeng and others in abstract painting, as well as Hu Jieming and others in new media. People customarily divide art into fine and applied art, which results in a “class” difference among academies. Precisely because of this, the Shanghai Arts and Crafts Institute, along with the Shanghai Theatre Academy (which also produced many “alternative” artists), has for a long time been considered “unorthodox.” Have you benefited from this lack of orthodoxy? And how have teaching methods and teacher-student relationships changed?

DY: The Shanghai Arts and Crafts Institute might also not be considered “unorthodox.” In the 1990s, it was a school absolutely without authority or prestige, and so the relationship between teachers and students was relatively more carefree, not so strict or solemn. Thanks to its more forgiving atmosphere and to its multidisciplinary approach, it has produced many artists, including Xu Zhen. It allowed many ideas and approaches to flourish quite freely. Of course, information was much more restricted then. I remember how Yu Youhan had to reside at school three days per week, so teachers and students really conversed and exchanged ideas. These days, many instructors rush home right after class, so there is not that space for close exchanges between teachers and students.

GY: Zhao Chuan once wrote in Shanghai Abstract Story (2006): “Ding Yi borrowed from Yu Youhan a catalogue of works by the French landscape painter Maurice Utrillo. For the whole night, he copied from the book in the dining hall. Ding Yi said that Utrillo is the starting point for his ‘Appearance of Crosses’.” How you do you see this?

DY: Utrillo wasn’t really completely the starting point for “Appearance of Crosses.” He was a teacher from whom I understood the techniques of Western painting in my early years. The part about the structure of cities and the variations of perspective came from Utrillo, but the “Appearance of Crosses” was really more inspired by Piet Mondrian or Frank Stella’s rationality and by their concise language of painting. That allowed me to glimpse another side of painting — that abstraction can be reduced to the most fundamental language of painting.

GY: In recent years your works have taken on a sense of “touch.” How did this change come about?

DY: The extraordinarily static quality of painting in contemporary artistic forms happens to be this “touch,” the part that moves one in painting. Good paintings are important. They are made up of metaphysical elements, like a certain spiritual disposition. Good paintings can move and infect people. At the same time, they can allow you to sense new perspectives and languages relevant to the world today.

GY: Xu Zhen, do you evaluate “good art” and “your own art” with the same criteria?

XZ: At MadeIn Company, there is only good art, not “our own art.”

GY: Your solo exhibition at the Long Museum last year transplanted and reproduced classic objects and sculptures from different cultures and periods, offering an open and plural space for interpretation. For me, the visual strategies and models produced by MadeIn Company are even more fascinating. You always seem to be purposely refusing original works. Why?

XZ: The blood to change reality is running in our genes.

GY: Before this solo exhibition, you received an invitation from Hans Ulrich Obrist to curate the collection exhibition “1199” at the Long Museum. The private collection was arranged in a grid, in that nineteenth-century European salon manner. The works were not categorized in the usual way, by year, media or theme, but rather according to the gender and number of figures in the works. This was highly distinctive, but for me, still too overly strategic — this tone was, of course, set the moment Hans Ulrich Obrist craftily made that invitation. I am more interested in knowing from what point in time and for what reasons you — who once “fought in flesh” — retreated behind the works, producing works indirectly or even using “stand-ins” on a large scale — and yet you are not resigned fundamentally to being an observer.

XZ: Actually this is a false question. Because whether you do it yourself or find “stand-ins,” it does not affect the quality of your work — nor does being academic versus being commercial.

GY: As the market bubble becomes more and more obvious, do you think new rules of the game will emerge? And what will they be like?

XZ: To consider whether the “market” is still important is itself a strategic commercial move. The market cannot be a strategy; it is a rule. The Internet age has changed everything. The profession of art is the profession that has faced change the most slowly.

GY: Speaking of change, over the last three years public and private contemporary art museums have been developing rapidly. Some artists have started to head south instead of heading north, to Beijing, as in the past. International art institutions and galleries have also chosen Shanghai as the place to present their artists in China. The stupor of the last twenty years in Shanghai culture seems to be breaking, with new artistic ecologies emerging. Yet we distinctly notice the problems behind this superficial image of prosperity. For instance, how investors lack intellectual confidence as well as steadfast determination in long-term investment; how museums lack strategy and systematic thinking in their collecting; how curatorial thinking and exhibition formats remain mediocre; how art administration and management is deficient; how museum operations and the design of museum spaces are disjointed; how there is a blank in tax policies and regulations regarding donations of artwork; how there are not enough independent curators and critics; and so on and so forth. As artists, you are the beneficiaries of this broader environment, but sometimes you also seem “exploited.” How do you two view the current situation? Can you offer some concrete suggestions?

XZ: Since 2000, there has been a necessary change in the structure of culture wherein the political will of the state has gradually ceded ground to a commercial consciousness. To talk about the construction of an art system in China, one must first resolve some fundamental problems in the primary and secondary markets. This includes at the very least: training collectors, broadening the collector base, changing collecting habits, linking up the domestic and international markets, and guiding the masses, among other things. Only when there is great market demand can we talk about specific problems like building for-profit and not-for-profit institutions, the social function of museums, the cultivation of talent. Otherwise, we will blindly follow a system that references the Western system and disregard the specific conditions in China.

DY: I feel that the current museum boom in China is like “crossing the river by feeling the stones.” All manner of champions pop up, and foundations keep emerging, yet we know that what is most lacking in the entire art market in China is an establishment of regulations on the macro level — for instance, how regulations about tax-free donations of artworks to foundations or museums have not been set, or how expertise in museum administrators is sorely lacking. Many private museums have this phenomenon in which the investor becomes the director, and there is a distinct lack of real administrators. At the same time, the commercialization of art, with art fairs and the auction market leading the way far too often, has stymied the circulation of art. This segment of the art galleries, for instance, is seriously affected. Or else newly founded museums are basically concentrated in first-tier cities like Shanghai and Beijing, while in second-tier cities contemporary art is still something that is part of a really small crowd. Aside from this, we can also see how the power of theory and criticism is really deficient, with very few independent art critics. Meanwhile, there is a lackadaisical appointment of curators.

GY: Nowadays, art fairs and galleries have gradually taken over the role of traditional museums, and they can, moreover, interface seamlessly with the commercial market. Around the world, museum collection budgets are being cut, while newly established public museums in China have no budget for collecting. What advantages do you two see in the new museums?

XZ: Currently, the development of private museums is suited to China; that’s our advantage. Given that there isn’t much government support, paying out money yourself is the most solid way to go.

DY: Aside from being relatively faster, newly established museums also have a certain amount of financial resources for exhibitions — this is the advantage. But they face other problems, like their standards in choosing artists, or the procedure in which works are collected; especially in the private museum system, works for collections are often directly obtained from the artists, while normally they should be bought through galleries. At the same time, what perplexes artists is that these works, which should be considered part of a museum’s permanent collection, every now and then reappear on the market. This is a big challenge faced by the new museum system in China.

Gong Yan, you are the director of the first [state-owned] contemporary art museum in China. Is there competition between public and private museums? What is at the core of this competition? What are the advantages to a public museum?

GY: The ultimate challenge between public and private museums stem from cultural systems of value and the capital that supports them. Public museums do not have a long-lasting advantage, since everything in the end depends on the will of the government. Yet currently, as far as the Power Station of Art (PSA) is concerned, the advantage is oriented toward intellectual research and the public good in a stable and enduring way. In the future, the PSA hopes to raise more financing from private sources by establishing a foundation and a board of directors in order to counter-balance the various limitations of government funding. As for the museum system, first we need to emulate the mature museum system in the West — not a selective emulation, but following the recipe. Then we can trim and add to it, creating and inventing according to our “national conditions.”

For example, over the last couple of years, abstract painting has repeatedly been featured in many large-scale exhibitions that have sought to reorder and rethink its history [see “Calligraphic Time and Space” at PSA]. Ding Yi, do you think there is a need to present an idea of “Chinese abstraction”? That is, to establish a system of Chinese abstraction through this overarching idea of classical Chinese thought and forms of artistic expression?

DY: The cultural environment we are situated in today is itself hybrid, complex and plural. It is difficult to have a purely regional artistic style or concept that is divorced from the international environment. In a certain sense, we can never return to this original body of traditional Chinese culture. We must face a new reality and seek out new breakthroughs — and not merely search for the origins of artistic language in tradition.

But, what I really want to know is how do you fix exhibitions? What is the system of evaluating the content and focus of exhibitions? Recently, the PSA hosted a solo exhibition of the late artist Datong Dazhang, which more than anything seems like an example of a [broader] phenomenon. As a contemporary art museum, do you focus more on reevaluating art history?

GY: All our exhibitions are appraised and decided upon by the academic committee, normally two years ahead of time. As for the overall direction of exhibitions, this is decided as a group every three years, after which it becomes our long-term research focus. History is always curated — and belongs to the majority — while art is intuitive, and belongs to the few.

Datong Dazhang was our first archival exhibition focusing on performance art and the politics of the body. The artist is respected but almost forgotten, so to revive him in a way served as a “magic mirror” for a series of exhibitions thereafter.

To conclude: do you believe a “Shanghai-ness” exists, and if yes, what is it?

DY: “Shanghai-ness,” I feel, is about capaciousness. Many fields in China are just entering into a stage of development with old models needing to be replaced. Under conditions of limited possibilities, standards are established, and through such work, we enable people to see and accept these standards. Such organizational work has no direct relationship to personal creation, but it does allow one to understand and grasp the distinctive characteristics of this new age. Both “Chineseness” and “Shanghai-ness” have entered a stage where they cannot be ignored.

GY: In my perspective, so-called “Shanghai-ness” can only be fully manifested in the environment of a city-state. It represents something independent and capacious and is essentially different from the national consciousness represented by “Chineseness.” It is an opposing force that ought not to be compatible. Yet as far as the development of culture is concerned, it is always better to be relaxed, free-ranging and autonomous.