Enrico David’s vision is a multiform and decentralized one, dissecting and disintegrating whatever it is turned on, a gaze in which everything signifies incessantly and repeatedly. With an inevitable drive that perennially shapes spaces of dissent, it is always at grips with the non-objectifiable. From painting to sculpture to installation, from collage to drawing and gouache, and even writing, the whole of David’s artistic practice has displayed a singular tendency toward the improbable and the unexpected. Drawing on craft techniques like embroidery and the vernacular of interior design, David exploits the functional potential of these practices in an attempt to organize and structure the chaotic nature of his emotional response to reality. His eclectic vocabulary has always been focused on a continual “giving [of] form to the instability of feelings and their impermanence,” as the artist himself has declared on more than one occasion.

In line with an irremediably nomadic nature, what starts out as a drawing or an image on paper leads in different directions, confirming David’s perpetual condition of instability and his persistent incompleteness as his physical and semantic precondition. The images intersect; they pass through the same places again, approaching or drawing apart and returning even after a distance of years. Each intersection opens a new perspective on the other.

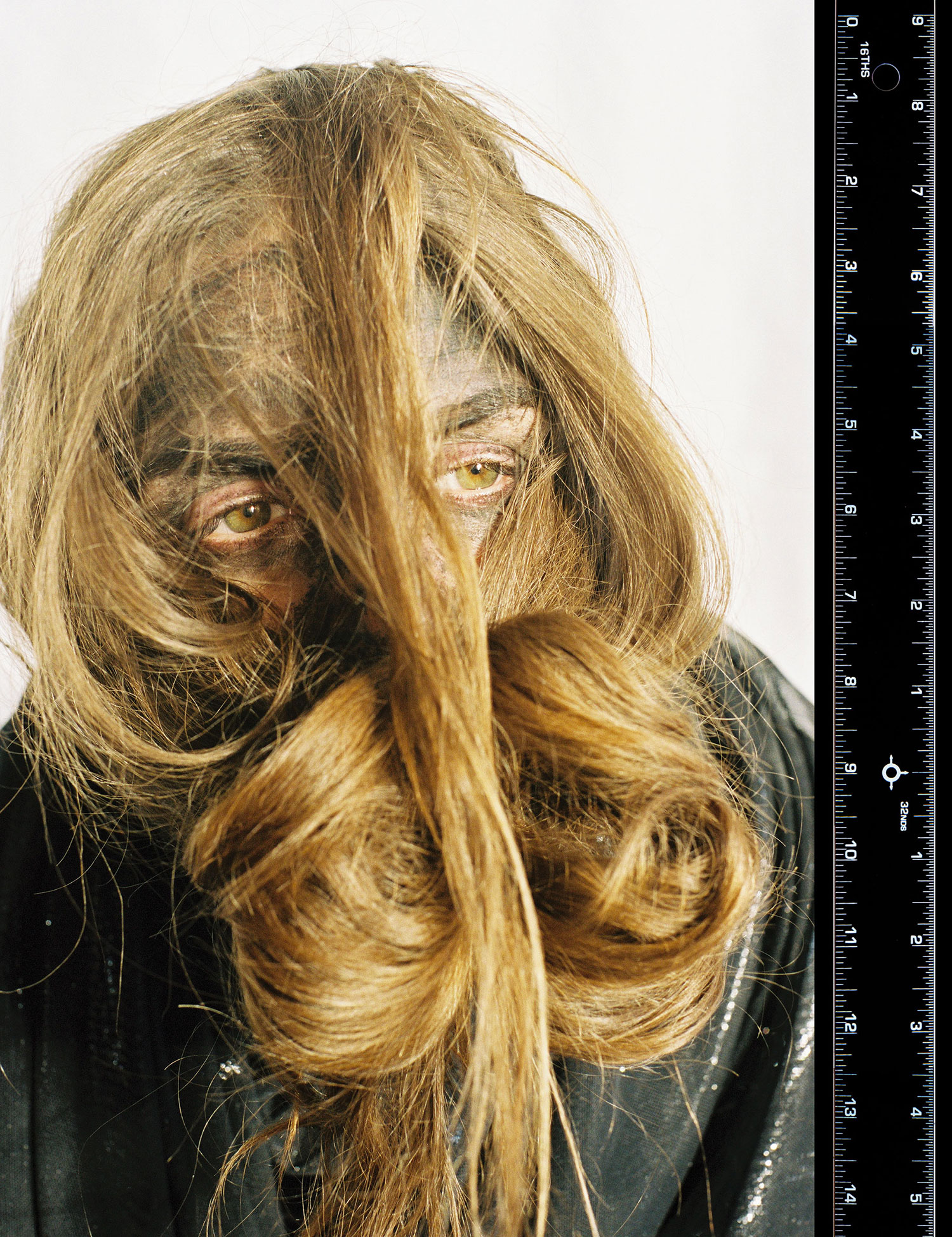

Right from the start, Enrico David has been continually exploring a possible representation of the human body, a body stripped of its drives and reified precisely because it can be divided into infinite segments. As Jean-Luc Nancy has written, “Bodies, in the end, are also that — head and tail: the very discreteness of the sites of sense, of the moments of an organism, of the elements of matter. The body is a place that opens, displaces and spaces phallus and cephale: making room for them to create an event (rejoicing, suffering, thinking, being born, dying, sexing, laughing, sneezing, trembling, weeping, forgetting…).”

Large canvases like Cora (2009) and Dinnisblumen (1999) — embellished with engaging and seductive titles for which David became known at the end of the ’90s — gave rise to a number of intensive and inseparable variations. His work followed an order of proximity to the degree in which the return of the one instantly relaunched the other as well. Imprisoned by needle and thread in a permanent emotional apathy, icy and vulnerable, the subjects had faces obliterated by giant orchids and gaudy butterflies. In a sinuous and serpentine movement, they froze an impassibly enigmatic body that derived the force of balance from its acrobatic postures. Later his work increasingly made use of a form of mutilation and hysterical segmentation that consumed all morphology, either erasing or destabilizing its places and functions.

Blending a wide range of idioms (from Mondrian’s Neo-Plasticism to Constructivism and Abstract Formalism), the tapestries in the series “Evenly Suspended Attention” (2004) show precisely this form of dissemination of the body. Between organ and organ, between fragment and fragment, they plunge the image into the reality of its own existence and, at the same time, formulate a body of language torn to shreds and reduced to a babble of meaning. Here the metaphor employed is that of the absent verb: fragmentations, more often traces without remains. When the real is not capable of standing as such, a second meaning becomes necessary to prevent the dissipation of every sense and the intrusion of nonsense. In other cases, hypertrophic body parts let themselves be seen as prosthetic extensions of an absent body, as in a famous story by Edgar Allan Poe. “Loss of Breath,” a famous story by Edgar Allan Poe, tells of a man who literally loses his voice and, looking for it frantically in his hotel room, can only find “a set of false teeth, two pairs of hips, an eye.” Even more frequently, the absence of the body reveals a numbness of the senses. There are works that display a scar which is the fruit of disquiet, show cuts and fissures and expose their artifices and hysterical contractures. Sublime and bold, compromised and compromising, they outline a somatic cartography that proceeds by isolated fragments, revealing and affirming a potentially chaotic, hybrid and above all unyielding “body.”

Chicken Man Gong (2005) is neither man nor chicken and perhaps not even a true gong; it is in reality a sort of hybrid spirit. It does not cancel the difference of nature but, like an acrobat racked in a perpetual feat, installs that difference with its own athleticism. Presented at the Tate Gallery as part of its “Art Now” program, it is a public sculpture that, in acting as a ritual instrument as well, continues to raise questions of authoriality and identity.

On the other hand, in the series of 23 gouaches that comprised his 2007 exhibition at the ICA in London, the confines of the body are twisted and dilated beyond chests swollen with anxiety to such a point that they become a Shitty Tantrum (2006-2007). Titles that sound like verbal statements, grotesquely distorted faces, traumas and fractures: the empty shells of the formal and narrative stereotypes now incorporate each time an identity and a history through an installation of discourse precisely where the body is missing.

In the same exhibition, Ultra Paste was presented for the first time. This installation reproduces the bedroom designed for the artist by his father in the early ’70s and echoes the structure of Vieille femme et enfant, a collage by Dora Maar from 1935. In the intimate complicity of this place, a harsh exposure of the self, private memory and unknown memory, that of another artist, touch one another. It is in the contact of their breaking and entering, one through the other and one into the other, that lies the prodigious effect of what has to be forgotten and lost in order to be able to remain in a different way.

In Enrico David’s work, personal memories, declinations of eventualities, literary allusions and private tragedies are grafted onto a dictionary of visual references that range from art deco to the applied arts, from the Wiener Werkstätte to Joseph Beuys and much more. In Bulbous Marauder (2008), for example, he makes use of Commedia dell’Arte and Harlequin’s multicolored costume — a symbol of the endless drift of identity — to dress up scrotal sacs. Their bulging, sagging and formless shapes, elevated to the function of festive lanterns, are an emblem of matriarchal suffocation. “Mother is a figure of speech,” said Angela Carter’s Eve; the mother is the sole generator of forms. And, as Mikhail Bakhtin emphasizes, the harlequin is not simply a melancholic fool. In fact, beyond his cosmetic mask he helps to rediscover the word: he helps a stutterer “deliver the word” by deconsecrating language and transposing it onto the material and corporeal act of birthing. In Enrico David’s practice, the use of language, whether represented or written, is also seen as a means of interpretation, translation and imitation. It offers the possibility of giving physical form to the need for discontinuity, interruption and abuse that are fundamental in his work.

At times it is a question of a vanished origin, at other times the words happen to clash with the images, and even before turning into something indissoluble they spread out within a story. In 2009 Enrico David was shortlisted for the Turner Prize following his two solo exhibitions “How Do You Love Dzzzzt by Mammy?” (2009) at the Museum für Gegenwartskunst in Basel and “Bulbous Marauder” (2008) at the Seattle Art Museum. The second Italian artist after Giuseppe Penone to be nominated for the prize, he arranged a cast of characters on a black stage in a sort of petrified scene. Egg men that rock backward and forward (based on a toy designed by Koloman Moser in 1905), a wearily oblong rag doll, a frantically beaten drum: a collage of memories, or more simply nightmares, are left to their own devices. Absuction Cardigan (2009) is the effect of a structural arrangement that invites the viewer to read the formula of legibility itself. The installation addresses the criteria of inclusion and exclusion, the wholly arbitrary borders between what finds a destiny and participates in the formal game of order and what, equally arbitrarily, is excluded from it. Scattering signs, symptoms, clues and varied testimonies that in the representative artifice put on a sort of theater, Absuction Cardigan stages the defoliation, the anatomy of a grammar, and in doing so promises the transitivity of the gaze and thus of the discourse. Once again we find a sort of installation of language, precisely where the body lacks an origin filled with a predicate of identity.

The group of works presented at a recent solo exhibition at VW (VeneKlasen/Werner) in Berlin make use of a virtuous silence and continue to investigate those limits of identity and the frontiers between the self and the other. Surfaces and volumes, limbs, heads and tails give substance to “figures” devoid of choice, with a vacillating essence that David himself has defined as “not yet ready to come into the world.” These are figures in the process of becoming where beauty and vacuity pursue one another in their circumscribed fragility. They pass into the forms and shake them off with a single gesture; and in this very spasm, between vanishing and persisting, radically bind the image to its reality of appearance. In some cases, the subtle dismembering of the subjects loses its own laborious weave of expressions, thread by thread, in order to produce abstractions. In others, the loss of tints and consequent fading surfaces congeals their breath in an agitated manner. They are figures through which the artist recomposes his own “physiology” of the word, before or after any attempt at verbalization. They meditate on the language of the figural, on its limits and on its inability to speak. It is a stopping, a deviating of the descent of the discourse by tearing the signs away from their denotative value. What they now say is precisely the intermediate, the uncertain and the unnamable. They speak a constantly extended secret that prevents the subject from fulfilling its destiny by merging with a predicate.

One might speak of a sort of rehabilitation of hysteria as poetic knowledge of the body, of an incessant revolt against something that comes from an outside or from an excessive interior thrown to the side of the possible and the tolerable. Something that is very close and yet cannot be assimilated. Like Palazzetto Tito, Venice, a city eternally losing itself, where the water offers beauty its double. Brodsky said that in this city there are many occasions on which you shed a tear. If beauty is a particular distribution of light, one more congenial to the eye, a tear is the way in which the eye — like the tear itself — admits its inability to hold on to beauty. Here, Enrico David’s vision has literally furnished this space of the bourgeois subject, gradually depositing in it the metaphors of its legibility.

Rita Selvaggio: “Repertorio Ornamentale” is the title of your recent solo exhibition in Venice conceived expressly for the spaces of Palazzetto Tito, a stately home and once the labyrinthine residence of Venetian artists. Between this interweaving of presences and absences, of distortions and superimpositions, I’d like to talk to you about what your work has put into effect in this particular context.

Enrico David: The exhibition had initially been conceived as a second stage of my recent solo exhibition in Berlin. The nature of the space has helped to galvanize certain aptitudes implicit in my work and possible evolutions/de-evolutions of some works in particular. The need on the one hand to integrate them with the physical structure of Palazzetto Tito, and on the other to try to establish a correspondence with its historic nature as a residence, using aspects of the vernacular of typically Italian interior design and decoration, which I have in any case often invoked in the past.

The guiding thread of this series of works is language, in its guise as a means of interpretation, translation and imitation rather than communication. It is my first solo exhibition in Italy, the country of my birth, with works produced during a year spent in Switzerland after living in London for 23 years. Every idiom, every thought that I have developed about my work has been conceived primarily in an acquired language. This linguistic experience has undoubtedly contributed to the creation of a parallel in the “unstable” and in a sense nomadic character of my creative process — in its physical manifestation as well as in its semantic motifs.

RS: Your exhibition at VW in Berlin consisted of images and enigmatic representations of the often distorted and fragmented human body. Semblances that evoke a disquieting condition of evolution and entropy, an inherent awkwardness and inadequacy. Can you tell me how their further transformation came about, or about the process of evolution you mentioned?

ED: If it is true that instability and uncertainty are typical of any questioning of the sense of belonging, in my experience the status of a picture, a drawing or a sculpture is in parallel, often subject to a probable revision. Working in Basel over the last year has undoubtedly been instrumental in the realization of the works in Berlin as well as in Venice, in their appearance of fragmentation and apparent imminent dissolution. Living here I have regained a sense of extraneousness, and under these conditions the work has begun to display different properties, more those of the physiological character of language than of the theatricality of content and narrative. I’ve rediscovered the pleasure of living in a country where they speak a language I do not know, and so one has the sensation of acting unobserved. In a certain sense the opportunity to show in Italy has instigated an alternative fate for some of those images, in accordance with that process of linguistic interpretation of which we were speaking before. So the image represented in a painting started to look to me like a console table, while another collage painted on canvas seemed inevitably destined to turn into a rug with two poufs. The language of design provides a sort of existential and formal scaffolding, a mitigation of what appears incomplete, inadequate and dysfunctional, offering them a possible integration into everyday life. But it is also a way of bringing into question the definition and the implicit expectations of painting, of sculpture, and subjecting them to a kind of molestation.

RS: Literary recollections — André Gide, Dora Maar, Koloman Moser and Oskar Schlemmer — or the memory of Sonya Delaunay’s textiles serve as the inspiration for the lampshades in “Bulbous Marauder.” Is there some echo in the works that inhabit these rooms too?

ED: The work enters the world as a testimony, to tell me who I am, and to change it. To this end I appeal to a visual, literary and human repertoire, accumulated and in continual accumulation, that over time ferments, is transformed and transforms me. That reflects a sense of harmony, or of aspiration to it. But also of dissent, of emptiness, of darkness, of desire and union. Of hysteria and conflict. Of ambivalence. There is always an echo of voices in the things that one does, even if they are just faint dialogues or adoptions of a position. Properties of the materials, the handling of things, the leaving of marks with dirty hands, the sign of time that causes decay. Everything reflects a source, even if it is unknown or unfamiliar. Getting used to the danger.

RS: On many occasions your texts accompany the route through the exhibition. Almost like a set of stage machinery that reflects the magnetism and the ambiguous vagueness of your titles. Is there some kind of connection between the image and the word? Does a syntactic relationship exist metaphorically?

ED: Writing also plays a role of scaffolding, of orthopedic support for the visual language. An inconstant, imprecise aid that bends back on itself informs me about what to do and is informed about what has been done. Pseudo-narrative in places, description, reflections on thoughts I had during the production of something. Coincidences and memories of things read that seem to have been written for the occasion, and celebrating them by modeling them, expanding them, altering them and at times seeing them slip into the unsuitable. I’d like to be able to think about it in as open a way as possible, exposed to accident and interference as much as a line drawn in pencil. Bending it. The sound of the words one next to the other, from form to content. Overloading the work with meaning is a strangling of its potential flow of energy, of its “unfolding.” But the fact remains that the written word can constitute an attempt to complement this flow. In a certain sense the writing is for the work, not for us.