Sheikha Hoor al-Qasimi, recently named curator of the United Arab Emirates National Pavilion at Venice, is a rare breed. Not only did she grow up alongside a nascent art world in the United Arab Emirates, she also had a hand in sculpting it. When the now-celebrated Sharjah Biennial was born in 1993, she was just thirteen.

In 2002, freshly graduated from the Slade School of Art, she journeyed to Documenta 11. The Okwui Enwezor-curated extravaganza stimulated her to ignite the international potential of the Biennial on her doorstep. Taking the programming reins of Sharjah Biennial 6 in 2003, she turned the event, and the Sharjah Art Foundation that it spawned, into the progressive-minded-yet-community-inclusive powerhouse we know today. In less than twenty years, a time span overlapping her own burgeoning adulthood, a cultural infrastructure literally sprouted under Sheikha Hoor’s very eyes.

That’s how the story generally goes. But this is only a partial tale. Sharjah was not some blank slate from which art sprang ex nihilo. If today Sharjah is a cultural doyenne in the Gulf, it is thanks to fertile ground tilled by an enlightened, history-sensitive ruler (Sheikha Hoor’s father — a prolific author and double PhD-holder in history and geography) and homespun initiatives harking back to the 1980s when the UAE was still very much a fledgling nation. “1980 – Today: Exhibitions in the United Arab Emirates,” the title of Sheikha Hoor’s UAE National Pavilion show, explores the forgotten histories of this underexposed period. Uniting fourteen Emirati artists, the exhibit embraces the pioneering work of the Emirates Fine Art Society — a non-profit institution founded in Sharjah in 1980, instrumental in training artists and nurturing talent.

How did you undertake crafting the theme for the National Pavilion?

When first invited to curate the UAE Pavilion, the idea came to mind immediately. I said, “This had to be done.” I grew up going to Emirates Fine Art Society exhibitions. In some of the catalogues from the 1990s, I find my own paintings! I think it brought me to what I am doing now. To give you a sense of its impact, the Emirates Fine Art Society was also crucial in the development of the Sharjah Biennial, and continues to have a profound influence on the community today. In “1980 – Today: Exhibitions in the United Arab Emirates,” I am looking at the emergence of contemporary art practices in the UAE over the past four decades. While I have worked with several of the artists before, in this exhibition my focus will be more on the artworks rather than on the artists themselves, in order to show the diversity of their practices. This approach also allows me to make connections to the history of the art scene in the UAE at this period.

How do you feel about expectations for you to “reproduce” your Sharjah successes in Venice?

I am excited to bring my experience from Sharjah to Venice and to have this opportunity to share an under-recognized moment in our cultural history with an international audience. At the same time, it is important for me to make sure the exhibition is brought back to the UAE. I suppose you could see this as an approach similar to how Sharjah Art Foundation engages with local, regional and international artists and communities.

How have you reacted to Okwui Enwezor’s theme of “All the World’s Futures”? It seems to resonate with Sharjah Biennial 12’s title “The Past, the Present, the Possible.” Do you see any points of intersection?

Enwezor has explained his approach to “All the World’s Futures” as “a stage where historical and counter-historical projects will be explored.” So the UAE Pavilion’s exhibition should fit nicely in this context. There are certainly points of intersection between what I am presenting in Venice and Sharjah Biennial 12: three of the artists I selected for the exhibition in Venice — Hassan Sharif, Mohammed Kazem and Abdullah al-Saadi — are in both the Pavilion and the Biennial. For Sharjah Biennial 12, curator Eungie Joo invited artists to engage with Sharjah as a city, as an Emirate and as a member of a federation (the UAE) that, while rooted historically to places and peoples, continues to consider the future while reflecting on its past. This process requires looking back and understanding the history of trajectories (artistic and social), both for the UAE and internationally. While very different in their approach and scope, both exhibitions have crucial relationships to history and research.

Your work at the Sharjah Art Foundation is highly contextualized within the community, and you have done much to anchor the Biennial there. Venice, in contrast, is by nature decontextualized; it tends to be more of a snapshot. How has this impacted your approach?

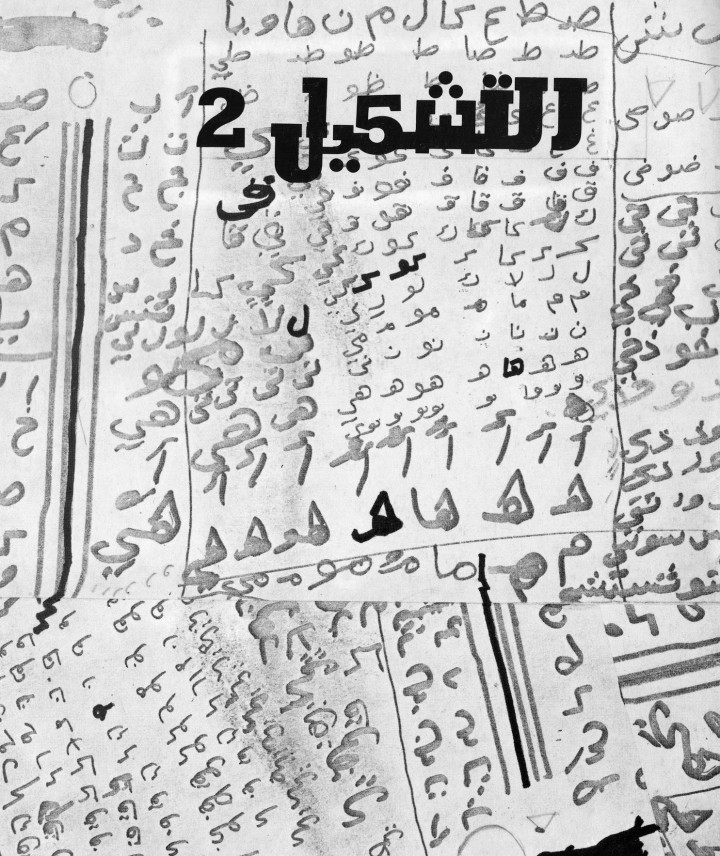

In order to create a context for the Venice exhibition, I have spent the past year intensively researching exhibitions and art practices in the UAE from the 1980s to today, using archives of newspaper articles, artists’ writings, catalogues as well as interviews with artists and cultural practitioners. Rather than taking a monolithic or one-sided approach, I wanted to create a more multifaceted narrative, exploring a range of Emirati artists from different generations, backgrounds and methods. The exhibition will draw connections between generations and collaborators, as well as the shift between modernism and contemporary work in the Middle East. It is not, however, a thematic exhibition. Both the presentation and the resulting publication will provide an insight into a context that, while being unique to the UAE, also draws connections to parallel practices and approaches around the world.