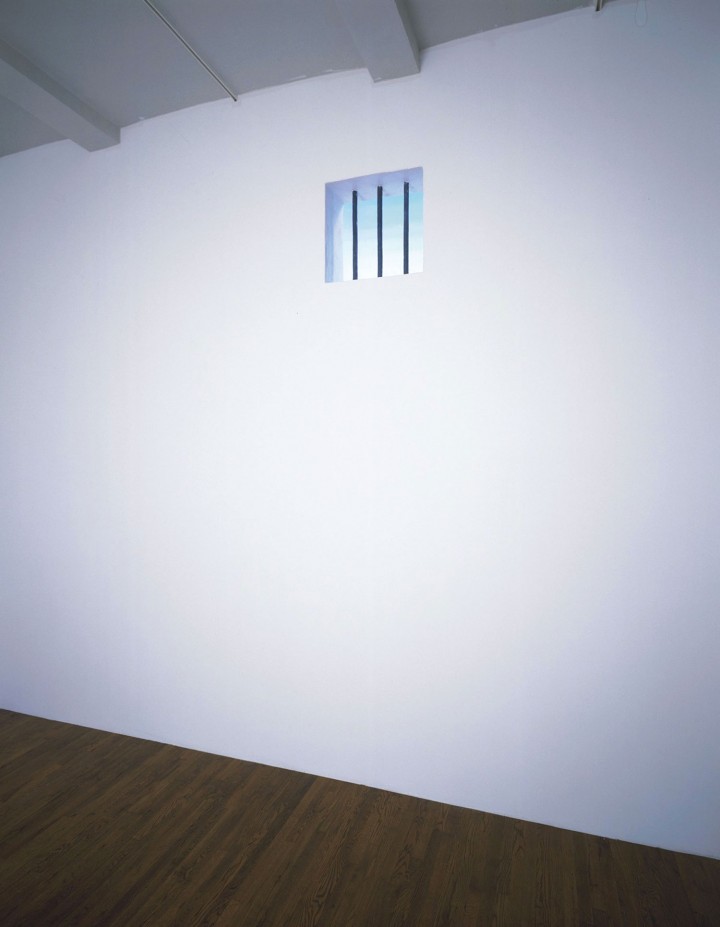

The US economy accumulates ever more debt, the unemployment rate and housing crisis have not improved, and the eurozone is in even worse shape, with Greece near default and Italy perhaps next. And yet the art market, which experienced a deep decline in the fall of 2008, continues to set new record highs. At Sotheby’s in New York at the major November sale, a Clyfford Still painting sold for $61 million, a Robert Gober edition of a jail cell window exceeded $3 million and Cady Noland’s work went above $6 million. Meanwhile, outside the building, behind barriers, was a raucous protest initiated by 43 full-time art handlers who claimed that their benefits were being slashed and their jobs were being downsized and given to part-timers.

There are continued protests at Wall Street and elsewhere, and critics correctly point out that there does not seem to be a specific agenda. But hearing the ear-deafening protest at Sotheby’s it occurred to me that there is clarity in this movement. It is larger than healthcare benefits and reinstituting jobs. It is about the growing divide between the very rich and the working class. Why are Wall Street bonuses so huge? What did the partners at Goldman Sachs do to deserve millions more last year? Did they invent a life-saving device? Create Facebook? What they did is lose trillions of dollars for individuals and other banks by reselling low-end mortgages and shoddy derivatives. But partners made money by cleverly packaging the deals.

Sotheby’s is a public company whose stock has soared with sales such as those in the recent auction. So why should they bother with 43 valued art handlers? Because slimming down the workers’ wages might shave a couple million dollars a year off the bottom line. This amount is not even equal to the commission of one good Warhol. Yet this is what most corporations are doing: eliminating jobs and reducing benefits while they sit on the most cash in history.

A collector friend and I were ushered out a side door after the Sotheby’s sale to avoid the protest. We passed by the crowd and both of us were dejected. We come from lower- and middle-class immigrant families. My father was a union organizer before he opened his own store on Grand Street. Perhaps unions had gotten too strong and American industry had become inefficient — to make a car required twice as many workers as necessary — but there has since been a seismic correction and the data show that we now have the largest recorded inequity between the rich and poor — in the US, Russia, India, China — almost everywhere. Hard-working people are losing jobs or experiencing pay cuts, have poor healthcare or none at all, and the Clyfford Still…

Hidden in all this art price hoopla is another story. The auctions riches are also highly selective. The Phillips de Pury & Company November evening sale in New York had high-priced items, and to enter this market most works were guaranteed by a third party. That means that if the guaranteed price is not reached, an outside source agrees to buy the work for that price. Not much risk for the seller, but in the end most sold for near the minimum.

Day sales were much less successful at all three houses (Christie’s, Sotheby’s and Phillips). Many works went unsold or sold well below prices achieved a couple of years ago. Artists with some real heat like Anselm Reyle and André Butzer suddenly cooled off. Of even greater concern were the starter auction September sales in New York, where weaker work is generally offered. Many works from the Phillips entry, aptly called “Under the Influence” and with generally very low estimates, still had many works go unsold. Even more alarming is that some dozen works sold for under $500, including $63 for a large sculpture by Toland Grinnell (est. $4-6,000 and originally much more), an artist who has shown at Basilico and Mary Boone. Same story for credible artists such as Uwe Henneken and Mungo Thomson. Everyone loses with such an outcome.

Exactly what happened here? These low-end sales have lesser work and lesser interest. But beyond this it points to a bifurcated market. When there is less interest nowadays in an artist there may be no effective floor. And when aggressive pricing for an artist’s work is not sustained, there is often little support going forward. Indeed the poor get poorer.

If measured by total auction sales or by the prices reached by artists such as Still, the art market seems unstoppable — vast amounts of money can be made. But the art market is mostly very selective, just like wealth in the world, where the divide between the rich and poor is widening ever more. The imbalance may have reached an inflection point. People are deeply angry. In front of Sotheby’s, Wall Street, Oakland, Athens — we are at a crossroads.